Private Paths and Public Space: A Comparative History of Grade-Separated Pedestrian Systems in Minneapolis and Montreal

A comparative history of Minneapolis’s Skyway and Montreal’s RÉSO shows how transit integration, planning priorities, and public-private dynamics shaped two distinct models of climate-controlled pedestrian systems.

Abstract

Minneapolis, Minnesota and Montreal, Quebec both began constructing grade separated pedestrian systems (GSPS) in 1962. Over half a century later, these privately funded quasi-public spaces have reached very different equilibria. The Minneapolis Skyway is controversial among the public, urban planners, and architects, while Montreal’s RÉSO is almost universally well-regarded. By examining the history of both systems in combination with both historical and contemporary accounts and present-day field observations of the two systems, factors that contributed to the divergence of the two otherwise similar systems are identified. Societal implications and theories around the future of public space in these cities are discussed. I conclude that the close integration of Montreal’s mass urban transit system with the Underground City is ultimately what made that system more successful, in terms of both public and private interests.

Keywords

Grade-separated pedestrian system, quasi-public space, transit, planning, Minneapolis, Montreal, skyway system, RÉSO, underground city.

Introduction

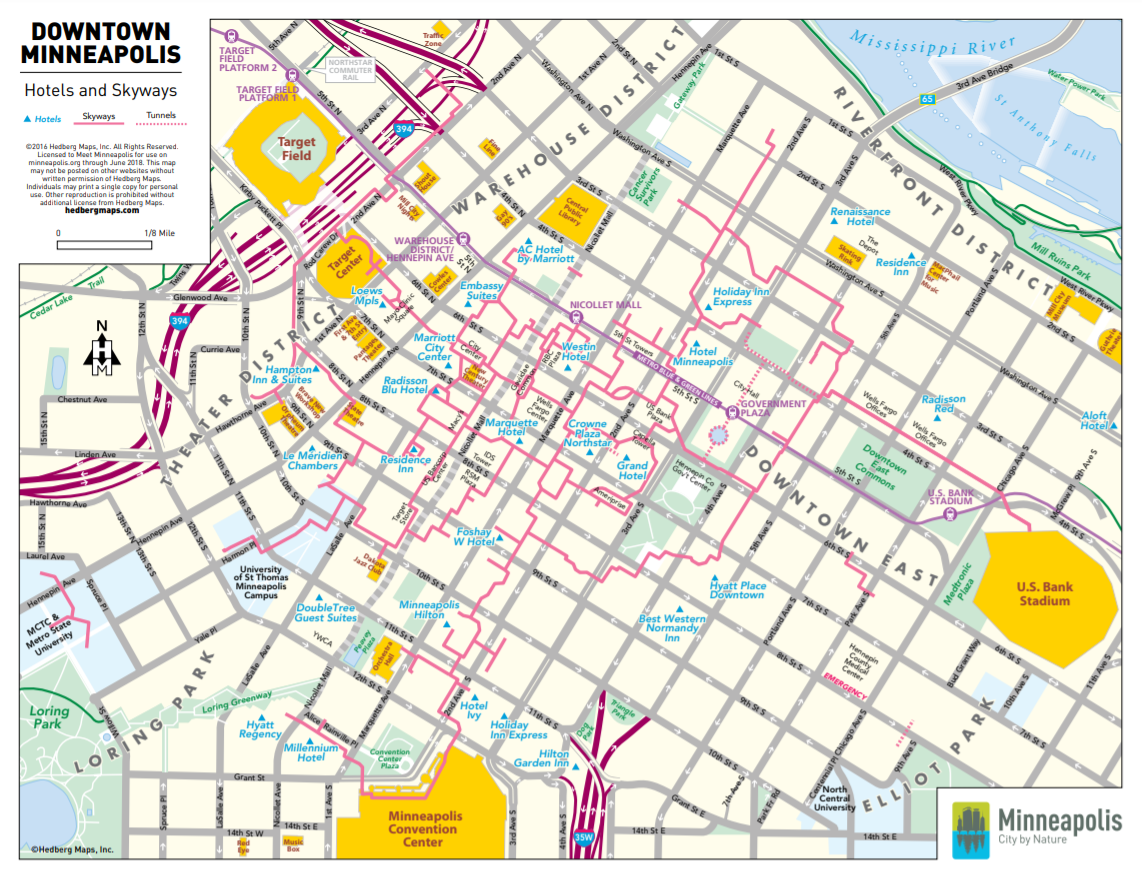

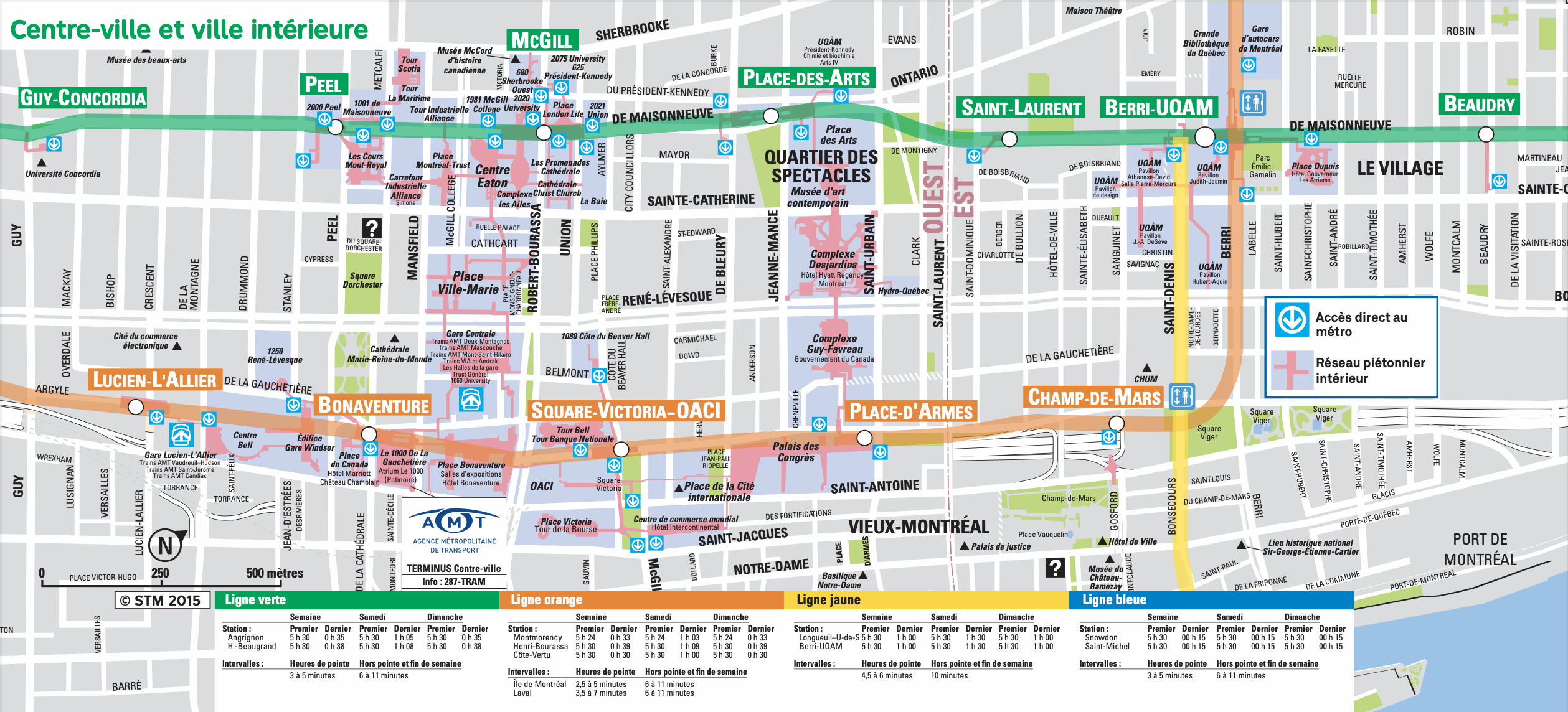

In 1962, two similar North American cold winter cities—Minneapolis in the U.S. and Montreal in Canada—constructed the initial segments of what would grow to become grade separated pedestrian systems linking buildings in central business districts and creating additional real estate. Minneapolis now has its Skyway System, spanning more than 10 miles of mostly second and third story climate-controlled passageways downtown connecting around 80 city blocks and over 150 buildings, including offices, restaurants, and shops, including three pro sports facilities and a church. Similarly, Montreal has RÉSO, originally called the Underground City, an even more expansive system set of at- or below-grade corridors spanning more than 20 miles downtown, connecting 4 universities, a cathedral, and a sports stadium in addition to nearly 2,000 shops and restaurants, 10 metro stations, two commuter train stations, and a regional bus terminal.

Both systems were funded almost entirely by the private sector but remain open to the public. The resulting space is part public and part private, a situation increasingly referred to as “quasi-public” in the urban studies literature. They may look like a public space and generally be treated as such, but their private foundation means they are only conditionally accessible to the public (Pratt 2017).

In the specific cases of Minneapolis and Montreal, the creation of these quasi-public spaces was a reaction of both public and private actors to the new urban issues of the day: expanding suburbs competing with downtown retail and housing, and safety and traffic issues caused by the increasing prevalence of cars in central cities. However, over half a century later, these two quasi-public experiments have reached distinct equilibria. Both remain under private ownership and are filled with shops and restaurants whose revenues pay for the construction and upkeep of otherwise unprofitable corridors. However, while RÉSO’s user base generally mirrors the city’s population, Minneapolis’s skyway system is primarily the purview of managerial class 9-to-5 office workers. Given similar baseline characteristics of the cities and similar reasons for the construction of the two systems, the reason for this discrepancy must lay in the particularities of the histories of the struggle between developers, city planners, and the public in each city.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section II, I define grade-separated pedestrian systems (GSPS), explain the reasons for their popularity in North American cities of the twentieth century, and present summary statistics for Montreal and Minneapolis today and in the 1960s. In Section III, I present a qualitative portrait of the two systems based on my own observations from visiting on workdays in January 2025. In Section IV, I analyze key architectural differences in the two systems. In Section V and VI, I present the chronology of the two systems and the associated controversies or lack thereof today, first for Minneapolis then for Montreal. This is the longest section and the core of the paper. In Section VII, I present theories on the implemented philosophies of the systems in the two cities. Section VIII concludes.

Background

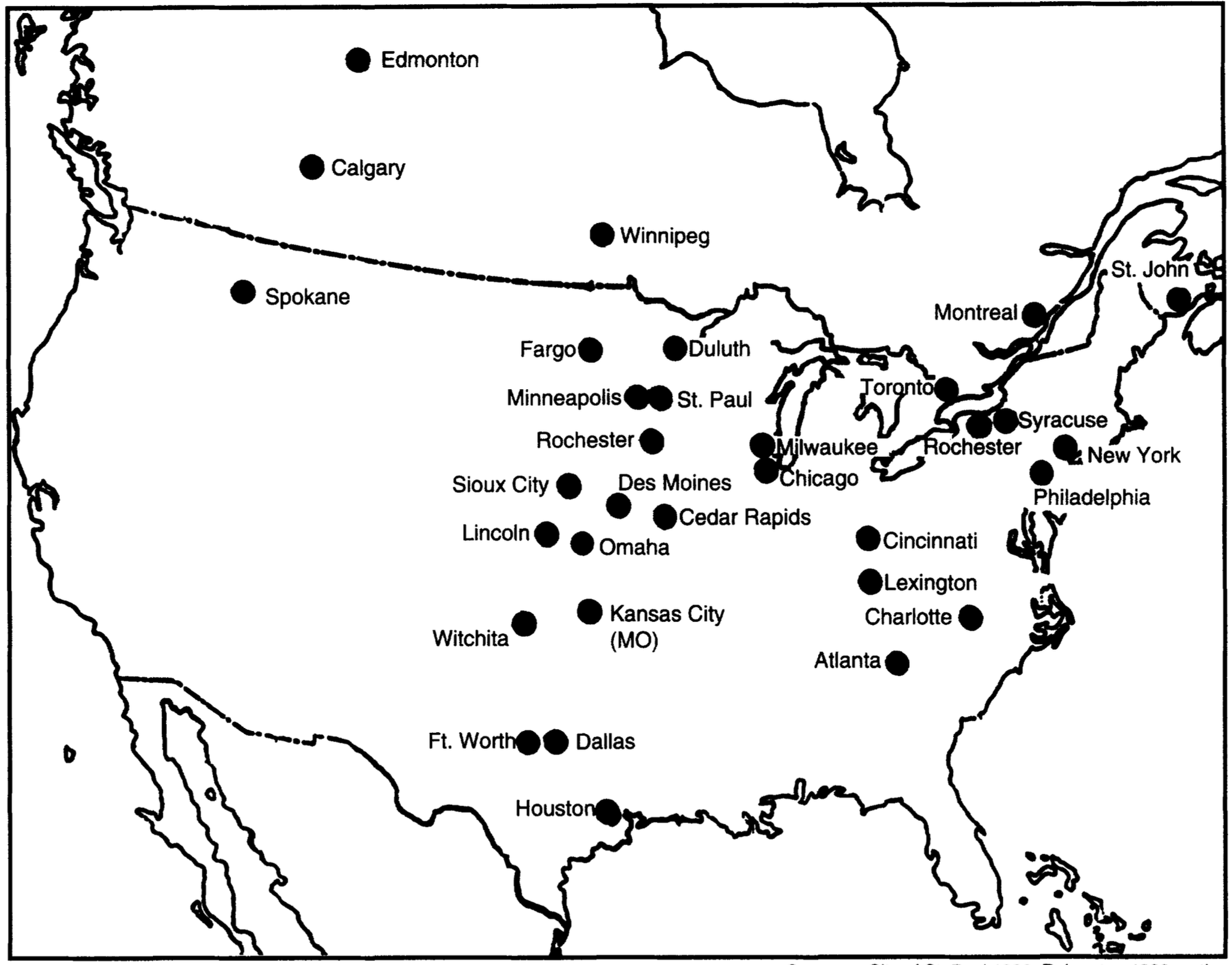

Grade separated pedestrian systems (GSPS) are generally enclosed, climate-controlled pedestrian environments in urban centers (Byers 1998a). The general reason for their constructions is debated, but their emergence in North America in the late 20th century was a response to urban problems, including the migration of people out of urban centers and into the suburbs (Cui et al. 2015). Particularly, suburban shopping malls competed with urban downtowns for retail traffic, enticing customers with a clean and temperature-controlled shopping experience. Supporting this story, popular media and opinion polls often cited climate control as the greatest virtue and supposed reason for the existence of GSPS (Boisvert 2007; Ratcliff 1970). Planners like the utopian idea of traffic separation at different levels, which was seen as a solution to increasing pedestrian-vehicle conflicts and deaths (Besner 2017). On the developer side, the primary reason was simple economics (Cui et al. 2013). Put bluntly, in such spaces, pedestrians are a “captured market” (Hopkins 1996, p. 69). Climate control may have made their use appealing to consumers, and their grade separation made them amenable to city planners, but they were built chiefly because they made money. GSPS had spread to at least 33 cities in North America by 1998 (Byers 1998a). One reason why Montreal’s and Minneapolis’ grew to be among the largest and most successful of these experiments is the fundamental value of climate control in such cold cities: Both experience average low temperatures below freezing five months out of the year. They also have a relatively high population density downtown to supply sufficient pedestrian traffic. Table 1 provides selected comparative statistics for the two cities. While Montreal is much denser, the two cities have similarly sized metro area populations and climates.

Table 1: Demographic and Geographic Characteristics

| Variable | Minneapolis | Montreal | Minn. – Mont. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metro population (1960 / 1961) | 1,482,000 | 2,109,000 | -627,000 |

| Metro population (2020 / 2021) | 3,694,000 | 4,291,000 | -597,000 |

| Metro area size (km²) | 15,703 | 4,670 | 11,033 |

| Metro area density (2021 / 2021) | 235 | 919 | -684 |

| Poverty rate (%) | 7.25% | 8.1% | 0.85% |

| January avg. daily high / low (ºF) | 24 / 9 | 24 / 9 | - |

Sources: (Centraide 2024; Benson 2024; Statistics Canada 2021; Central Minneapolis 2024; National Centers n.d.)

Qualitative Vignettes

On a weekday in January in downtown Minneapolis, the temperature is 15 degrees Fahrenheit. The streets are sparse, but dark figures can be seen walking across enclosed glass walkways a floor or two overhead. Defining the central business district—stretching from US Bank Stadium in the east to Target Field in the west and from Minneapolis Convention Center in the south to the Mississippi river in the north—sits the Minneapolis Skyway System. Entrances to this network are not well advertised, but you may notice that the Target store on Nicollet Mall has escalators leading to a second floor with a Starbucks and a glass hallway. If you follow small groups of people coming in and out, you will pass over a street and under a sign that tells you your location: “9th street and Nicollet.” On this second level, you may see a Minneapolis police officer or a U.S. Bank Center security guard outfit. The Skyway is quiet, clean, and safe. Its pedestrians shed their layers to reveal an unofficial business casual uniform. Continuing through a sequence of turns and straightaways in the building, you may pass an eye doctor, an empty lobby with expensive-looking chairs overlooking the (still quiet) city streets, a short hallway with elevators requiring key access, banks, coffee shops, and restaurants. You will likely find that you are in a Center named after a large bank, who also present their own retail locations in the Skyway.

If you stop and check the hours of one of the restaurants, you might be surprised that many are open only in the hours of an office lunch rush, from 11:00 to 1:30. After a few more clean white corridors devoid of retail space, you may pass over another street—this bridge notably missing that helpful navigational tool placing you on the city grid—and end up in a large skyscraper lobby with elevators to the ground floor and a help desk, also funded by the bank whose building you are currently in. Where you pass stairs, you will find a mechanized lift for ADA compliance, but if you will not find restrooms accessible to the public. The single stall restroom in Target is unmarked and effectively hidden. Restaurants in the Skyway will also not have any. They are more like mall food court stalls than proper shops, though unlike malls, no central Skyway association pays for restrooms, the plausible assumption being that the intended customers will be able to access facilities in your building.

Meanwhile, in central Montreal, the streets, though not bustling, are apparently crowded enough to support more street-level businesses. If you needed to buy snow boots to stay dry on the slush-filled sidewalks, however, Google Maps would direct you to a mall. Upon arrival, you notice it is below street level, in the Underground City. The walkways are much wider than those in Minneapolis, and there is much more pedestrian activity. A higher proportion of the shops are retail, and the people are certainly not all office workers. Unlike the Skyway, RÉSO is populated with panhandlers, and security is not so obviously a presence. You may find yourself by a metro turnstile, take the train a few stops, and again emerge in a similar environment, still underground, still surrounded by retail shops and customers without a clear unifying stripe. In further exploration, you stumble across Montreal’s regional train station, then Place Ville Marie, a central seating area in the day that becomes a popular dance floor and bar in the evening. Many areas are devoid of both retail and pedestrian activity, just like the Skyway. Also like the Skyway, these areas tend to serve as bank lobbies. Changes in elevation are much more common than Minneapolis’s relatively consistent second story level, with some sections layering four stories on top of each other, but signage is plentiful, and the location of the tunnels on the ground and underground floors is more easily navigated by GPS. Though not entirely seamless, RÉSO feels more like a continuous extension of the city.

Architectural Differences

These vignettes track my admittedly limited experience with the two systems. Apart from Minneapolis being above ground and Montreal being mostly underground, the most obvious difference I noted was that Minneapolis’s Skyway System was solidly the domain of the 9-to-5 office worker, an observation that is supported by various accounts in the popular press (Cui et al. 2015). Another major difference between the two GSPS is the presence of a Metro system in Montreal. Minneapolis has two Light Rail Transit Lines and one Bus Rapid Transit Line, but the stops outside are sometimes hard to access from the second story, and vice versa. Relatedly, the streets in Minneapolis tend to be wider, with more car traffic. Parking garages are also a more significant part of the system. For example, I did not find my way to one while wandering in Montreal, but I did so twice in Minneapolis. Indeed, because many parking garages are public, the connection to parging garages on the outskirts of the system are among the few parts of the skyway system that the City of Minneapolis funded (Daniels 2005).

Cui et al. (2015) summarize the literature on GSPS and identify eight architectural categories by which to evaluate their quality as public spaces. I found four of these categories to be noticeably different in Minneapolis and Montreal, all of which are closely related to integration of the system with the Metro: transportation, arrangement of entrances/exits, spatial structure, and operating hours. Though some of these characteristics have purely aesthetic elements that may not be strictly necessary for functionality, aesthetics also change how the space is interacted with. A place must be welcoming in addition to accessible to serve as a truly good public place.

Arrangement of entrances/exits

The entrances in Minneapolis are not well advertised. The skywalks are visible from the street below and indeed define the architecture of the downtown to be solidly modern, but to get there one must walk into a skyscraper, whose hours are more limited than the skyways. One building wrote on its glass doors “No Public Skyway Access.” Montreal faces some of the same problems, but the ten subway stops that connect to the system are well advertised and lead into the system.

Spatial structure

Though grade-separated, the structure of Minneapolis’s GSPS is not a good pedestrian system. It is architecturally viable only for office workers familiar with their personally well-trodden routes. For instance, one blogger and urban planner living in the Twin Cities who knew the Skyway System well enough to make a NYC Subway-inspired map of the system admits not to have yet traversed all eleven miles on foot (Hundt 2017). This urban planner resident’s lack of total familiarity with the System suggests ordinary residents may stay in their familiar sections of the Skyway with the same businesses, both because the cost of change in novelty is high, and because another path is likely impossible.

Montreal’s RÉSO is also quite confusing to newcomers. However, because the system is underground and occasionally at-grade, the pathways can go directly under streets or even directly open to them at street level, maintaining a more direct connection to the outside world. For example, signs may point to an exit to a main shopping street and counterpart to Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis. By contrast, landmark destinations in the Skyway’s signage are specific skyscrapers with no obvious connection to the city’s general street-level geography.

The ten subway stops connected to Montreal’s system are also a key to navigation. Like in Minneapolis, poor signage remains an issue. In fact, confusing elevation in Montreal changes allowed by the system not being confined to the second floor can make navigation by signage even harder. However, the best and most consistently indicated parts of RÉSO are the Metro stops. They are featured prominently on maps and, unlike in Minneapolis, are understandable to GPS mapping software. Therefore, it is possible to find your way to a location by locating the nearest Metro stop, travelling there, and using GPS to complete the journey. Businesses are eager to attract customers from the Metro, and the Metro wants to be navigable, so signage around stops also tends to be more than sufficient.

Operating hours

Hours remain a central issue in Minneapolis’s Skyway. The city’s official tourism website writes, “Most Skyway connected buildings are open until 6pm, Monday–Friday and are closed on weekends,” and warns users to, “Watch for signs that indicate shorter, or longer, than the usual skyway hours” (TOURISM). In fact, each building in the system determines their own Skyway hours. Users can enter and search for the hours of a specific building, but still “Skyway hours are subject to change at any time” (TOURISM). Moreover, because the Skyway is a network of buildings and paths, even if the destination is open, it may be impossible to reach through many entry points in the Skyway; its function as a GSPS for users outside of the standard office work week therefore fails due to lack of unity in both information and policy as a result of the domain of individual property owners (Sijpkes and Brown 1997).

By contrast, in Montreal property owners must give a public right of way during hours of the Metro’s operation, from 6am to 1am every day in order to get access to the subway station, meaning all critical corridors are open most of the day (Besner 2017). Besner (2017) calls the subway “the real release mechanism” for the Underground City’s development.

The Skyway System: History and Controversy

Minneapolis’s population peaked in 1950 and was on a downward trend when the Skyway was conceived and built in 1962 (“Minneapolis: An”). Further reflective of this trend, the largest indoor shopping mall in America, the Mall of America, opened in a suburb of Minneapolis in 1992, indicating a desire for climate-controlled shopping in the metropolitan area (“Mall of America”). In response, a property owner in downtown Minneapolis conceived of the Skyways to compete with modern suburban shopping centers and entice shoppers to come back to the city center. They drafted a plan connecting a parking garage to restaurants, department stores, and skyscrapers (Daniels 2006). Their 26-million-dollar investment, which was 6 million more than the cost of one of the buildings, proved in the end to be profitable. In 2006, the average city worker in Minneapolis was spending twice as much money on their lunch breaks as they did before the construction of the Skyway System (Daniels 2006; Thornton 2021). In the 1980s, lease rates in the skyway could be twice as much as at street level (Kaufman 1980 in Cui et al. 2013).

Corroborating this understanding, Byers (1998b) explains that a 1959 Central Minneapolis plan never mentioned weather in relation to a supposed GSPS, instead mentioning only its ability of separating pedestrians from vehicle traffic. A 1970 planning document again cited indoor climate control only as a secondary perk to the primary function of pedestrian-vehicular traffic separation (Byers 1998b, p. 155). To emphasize the lack of importance for climate on the supply side, one developer was quoted as saying in a 1995 interview “if the public thinks they need protection from the weather, let them. We’ll give them what they want as long as they keep spending money downtown” (Byers, 1998b, p. 160).

Municipal interventions

A Minneapolis city ordinance document from 2015 shows how stringent regulations had been backtracked or removed, including several provisions that would increase accessibility and alleviate some of the issues with the Arrangement of entrances/exits and Spatial structure. For example, the statement: “Skyways in new buildings shall be designed to facilitate access between street and skyway levels with a public entrance on the exterior of the building or access lobby [emphasis added]. Elevators, stairs and escalators linking the street and skyway levels shall be conveniently located with clear directional signs [emphasis added]” was amended to “Skyway corridors shall be designed to facilitate clear and easy access between street and skyway levels. Elevators, stairs, and escalators linking the street and skyway levels shall be located in such a way as to provide convenient, visible links to the skyway level from the adjacent street and sidewalks” (The City Council of the City of Minneapolis n.d.; Gordon and Palmisano n.d.; Amendment to Minneapolis Code of Ordinances 2015, p. 9-10). The clause looks similar, but it was crucially stripped of its stipulations of “a public entrance on the exterior of the building or access lobby” and “clear directional signs,” the two actionable and enforceable solutions to improve the public’s use of the space.

In other clauses, this document also uses such unenforceable language as “strongly encouraged.” When discussing signage—a major issue identified by many scholars as an obvious shortcoming of many GSPS—the document states, “All buildings that incorporate new skyways into the system are strongly encouraged [emphasis added] to install the standardized electronic information kiosk for the Skyway System on the skyway level of that building” (p. 11). Again, this qualification renders the ordinance unenforceable and potentially pointless.

The standard Skyway hours outlined in the document does seem to be enforced (though they are shorter and less regular than those in Montreal and centered around the Monday–Friday work week), but property owners are merely “encouraged” to keep their Skyways open beyond these standard hours of operation (p. 12). It is perhaps notable that in the same document, the council has successfully rallied around stipulations to improve bird safety (Ordinance, 2015, Dec 15).

Minneapolis’s current master plan, Minneapolis 2040 was adopted October 25, 2019. It admits they are privy to controversy:

Downtown skyways have been the source of debate for decades. They are beloved in extreme and inclement weather for their seamless indoor connections and are the focus of ire for their lack of navigability, their inaccessibility from the street, and their impact to street level vibrancy. Access to the skyways can be improved through additional high-quality connection points to the street, specifically at primary transit and pedestrian routes. Navigability can be improved through designs that provide transparency to the street. Tying skyway business activity to street level business activity while limiting skyway expansion can help create opportunity to improve street level vibrancy (City of Minneapolis 2019, p. 130).

They go on to list some promising action steps, including to “Require newly established retail uses in buildings connected by skyways to be located primarily on the ground floor with an entrance facing the street.” They are notably able to forcibly discuss bird safety (“Require transparency of skyway walls that meet bird-safe glazing definition in order to provide views into and to the outside that help users orient themselves”). However, some action steps remain inactionable. For example, the action step to “Encourage skyways as a transportation, rather than commercial system.” This language shows that Minneapolis is open to addressing the Skyway’s shortcomings, but their proposed solutions have been rendered toothless through political pressure (Minneapolis Department, 2019). In the end, birds can be protected, but a push towards a more usable public space fails.

Controversy in the skyways

Urban planning scholars and architects have consistently identified concerns with the Skyway System, though it showed no signs of stopping. Today, this debate continues among residents on blogs, online forums, and in the popular media.

Chief among concerns was the competition with the fully public, at-grade traditional street network. A 1998 doctoral thesis argues that GSPS in Minneapolis, Toronto, and Houston “helped to drain pedestrian life from city streets and sidewalks” (Byers 1998b). Another academic publication from 1992 writes “there is no doubt that the second pedestrian level is in direct and potentially damaging competition with the street” (Maitland 1992). This author notes that the Skyway System was regarded in a contemporaneous planning document as downtown’s second most important pedestrian facility, after the traditional shopping street of Nicollet Mall. Under my scientific observation, this street, like the rest of the network, was decidedly less populated than the Skyway. Retail establishments were sparser, at least compared to similar Montreal and other American cities. People on the street were also less likely to be perceivably white than skyway inhabitants. In 1987, a Minneapolis-based rock band known as The Replacements released a song called “The Skyway,” showing both the system’s cultural relevance and corroborating the experience of a fundamental segregation between the Skyway and the at-grade streets. The song’s narrator, freezing outside, sees someone up in the Skyway and hopes they’ll “meet out on the street.” Later, he finds himself up in the skyway and then out on the street, resigning “there wasn’t a damn thing I could do or say // up in the skyway.” Though this inconvenience in the song was used as an ironic device, recent public sentiment is more critical of the same situation. As a 2024 article explains, “Once celebrated, the skyways of Minneapolis are now being blamed for downtown’s empty streets” (Lileks 2024). A 2018 article recommending the top ten restaurants in the skyway again indirectly articulates this situation with “Out-of-towners can be forgiven if they stroll along the frigid and empty sidewalks of a prosperous-looking downtown Minneapolis and wonder where all the people have gone. Two words: Look up. They’re in the skyway system” (Nelson 2018).

A further concern is that the Skyway System is exclusively for office workers, corroborating my personal observations. One 2016 news article articulates “Minneapolis may be known for its skyways, but they weren’t designed for visitors, but for 9-to-5 office workers.” He continues, “anyone who’s tried to give directions to a newbie finds that it’s almost impossible to guide them by buildings or even streets because there’s often not a clear correlation” (Ode 2016). Indeed, while navigating the system, I found it necessary to just step out onto the very clear square street grid to get to different sections of the skyway even though a path did exist, and helpful bystanders did offer some help. Similarly, a Twin Cities resident grapples with a love/hate relationship with the Skyways in a personal blog. He loves that they are heated and culturally significant to the city, likely playing a role in attracting the Super Bowl there in 2018, but also names the competition with the streets, and hates “Most importantly” that “skyways are extremely difficult to navigate with ugly and unhelpful maps and signage” (Hundt 2017). Users on online forums are also not shy to share their opinion. One user wrote of a limitation they were willing to accept: “sometimes you have to go double the distance, but being in a (usually) heated skyway is totally worth the extra walk” (Valendr0s, 2015). Though, in my experience asking an employee how to get to a destination connected to the Skyway, she said it’s probably easier to just go outside. Another user bluntly described it as “A bunch of elevators you can't access to corporate banks and such, a bunch of restaurants that are only open from 11am-130pm, and a ton of empty space since vacancy is high due to WFH” (Hungry-Attention-120 2024). Yet another complaint was the lack of public bathrooms, a situation indicative of the public-private conflicts central to these spaces (bfeils 2024).

There are other related concerns as well. For example, a popular documentary podcast, 99 Percent Invisible, discussed the racial history of the skyway in a 2021 episode called “Beneath the Skyway.” In an interview, a black Minneapolis resident explains that, once a hang out spot for him and his friends, the skyway became increasingly filled with white-collar workers. He also felt an increasing police and security presence, to the extent that he, a young black man, stopped perceiving the skyways as “fun, or even comfortable.” (Thornton 2021).

It is important to note that public opinion is not rallied against the Skyways. For example, the owners of a popular Minneapolis restaurant wrote in a 2017 opinion piece: “While yes, there are empty storefronts, there are plenty of retailers and restaurants and bars and banks and branding agencies and software developers and all sorts of other businesses that are thriving downtown with or without skyways.” They claim that their restaurant thrived both on the ground and in the Skyway. “Folks do find their way to whatever businesses they want to support; when we took an informal poll this past weekend, we discovered they came by foot, car, bus, light rail, Uber, bike, scooter, and motorcycle. One person came on his longboard and yes, several found us via skyways” (Cynthia et al. 2017). They argue the tax money sent to the state was a benefit for the city, for example in its partial use to help construct the U.S. Bank Stadium.

RÉSO: History and Harmony

Montreal started similarly as a private development, the still central Place Ville-Marie. The railyards of the Canadian National Railway company in central Montreal were due for development. One author called the core area of the city “a sad spectacle: aging buildings surrounding a seven-acre eyesore, the pit-yards of the Canadian National Railway” (Ratcliff 1970, p. 426). The rail officials finally called developer William Zeckendorf, who in turn called middle-aged urban planner Vincent Ponte. Ponte saw an opportunity to realize a vision he had had for a while and which would become Montreal’s Underground City (Ratcliff, 1970, p. 427). He took Place Ville-Marie from an admittedly extensive isolated project to the seed for a utopian plan. He worked closely with Montreal’s Planning department to lay out a theoretical plan to realize his vision alongside that of the property owners (Besner 2007). Just like Minneapolis, what finally convinced developers was the ability to turn basement storage space into much higher rent retail space (Ratcliff 1970). Unlike Minneapolis, Montreal built a Metro soon after.

According to Besner (2007), the Metro was “the real release mechanism of its development” (p. 3). Montreal was able to use some of the revenue from the Underground City—over $7 million a year—to finance the Metro’s construction. The first line opened in 1966, just 4 years after the first linkages in the Underground city (Ratcliff 1970, p. 428).

To further contextualize this development, it should be noted that underground tunnels are expensive, quite a bit more so than skyways (Cui et al. 2013, p. 152). Besner (2017) reports that investment costs were on average 40,000 CAD per linear meter in Montreal. Though, considering that Montreal’s system is today larger than Minneapolis’s, the marginal benefit of more pedestrian traffic from a connection is ostensibly worth the extra marginal cost of extension. Logically, Zacharias (2000) found that a business’s profits are directly related to the amount of pedestrian traffic, and Besner (2017) playfully notes that public transit stations are increasingly among the most heavily trafficked places in cities and the world, sometimes an order of magnitude more than major historic sites like the Colosseum in Rome.

Montreal started off on a decidedly public foot. Sijpkes and Brown (1997) explain how Place Ville-Marie set the tone for a more public-friendly system:

While the pedestrian network of corridors provided an efficient way to pass under a busy thoroughfare and had the added benefit of eliminating the necessity of going outside in inclement weather, the storefronts added a considerable amount of animation to the corridors, enhanced the feeling of security and offered a source of revenue to offset construction and maintenance costs. The Place Ville Marie project set the tone for future underground or “indoor” development not only in Montreal but in many cities across Canada, introducing the notion that private enterprise could, and perhaps even should be encouraged to take advantage of natural pedestrian flows to create indoor space with an unabashedly public quality (Sijpkes and Brown, 1997, pp. 15-16).

Municipal interventions

Montreal continued this stance of shepherding the system towards an end of a usable public space. As described above, RÉSO was both started and developed privately and without an explicit Master Plan. However, later in the system’s life, the City of Montreal did implement several guidelines to control the outcome. El-Geneidy et al. (2011) explains how the 1990s city administration enacted a moratorium on further expansions of RÉSO for fears of siphoning businesses from the city’s main commercial artery, St. Catherine, and in response to preemptive concerns that the downtown retail market was saturated. The 2004 Monreal Master plan revisited the view and emphasized consolidation, advocating for improving interaction between the indoor and outdoor systems, universal access throughout the system, expanding wayfinding signage, and “capitalizing on the Indoor City to increase the modal share of public transportation” (El-Geneidy 2011, p. 37). Montreal’s 2007 Transportation plan once again realigns the consolidation and expansion efforts with the city’s larger goals (El-Geneidy 2011). Though there was no strict development plan, these changes, RÉSOlutions, and reconsiderations show how Montreal was successful in making sure the city was not harmed by the network.

Moreover, these efforts have also appeared to have been substantive. Sijpkes and Brown (1997) highlight the example of the presence of a large public atrium in another development connected to the Underground City, Complexe Desjardins. They write “The almost constant exhibitions, frequent TV tapings and community events in the atrium contribute to the sense that the main hall has become a genuinely public indoor space” (Sijpkes and Brown, 1997, p. 3). Once again though, this was all privately funded. Boisvert (2007) reports that only 4 out of 41 linkages into the public domain utilized public funds, all of which he claims the City had extraneous reasons for.

Since the Metro innately ties the Underground city to not a destination but primarily as an accessible mode of transit, market forces also played a role in correcting perverse antisocial behaviour on the part of the developer. Sijpkes and Brown identify a particularly clear example:

The Place Bonaventure link was one of the most notorious examples; here the designers effectively force-fed commuters arriving at the Bonaventure Metro and bound for Central Station or Place Ville Marie to continue along a bland tunnel to the center of their shopping concourse, change elevation, make an about face, return in the direction from which they had come, pass additional stores on the ground level, and, finally, to descend down a flight to gain access to a pedestrian passage under Rue La Gauchetiere (Sijpkes and Brown, 1997).

In short, the complex was so hard to navigate that it became economically unsuccessful. It was demolished and replaced by the still standing well-signed and well-trafficked Eaton Center (Sijpkes and Brown, 1997).

RÉSO as an amenity

Put simply, RÉSO is not as controversial as the Skyway System in Minneapolis and was met with praise from the beginning, gaining the title “city of the future” in a 1970 article that also presents a lot of the thinking on urbanism at the time.

Are cities doomed to be clamorous places of filth, fumes, danger, strangled by traffic? Not this one-where it never rains, never snows; where there is pure air to breathe and temperature never varies from a comfortable 72° F. There are no screeching sounds, no motor traffic. We speak of the city of the future: underground Montreal, which is living up to its claim of being ‘the pilot city of a new world’ (Ratcliff 1970).

More recently, Chatoney (2019) called it “an excellent example of what a successful public-private partnership between the city and developers looks like” (p. 14). Besner (2017) set out to identify the reasons for its success.[1] Montreal continues to pursue goals of sustainability and affordability even though RÉSO, likely because it is not causing problems, is not featured in their current master plan, Plan d’urbanisme et de mobilité 2050 (“City of Montreal” 2024).

It is important to note that there are some limitations to the Metro. Montreal decided to use a rubber tire system, which made it hard for trains to transition between above and below ground on icy tracks in winter, therefore artificially constraining RÉSO and the train to tunnels instead of being able to integrate with the surface of Montreal’s hilly terrain to a greater extent (Sijpkes and Brown, 1997). But the system has got more right than it has gotten wrong. As evidence of this success, RÉSO is a well-known tourist attraction, like the Skyways, while also retaining its primary function of climate-proof transportation for all Montrealers (McFarland 2015). In the words of one article, “A visit to the ‘underground city’ is a top item in any Montreal tourism guide, although asking a resident for directions just might get you the tiniest roll of the eye. That’s because to many Montrealers, the tunnels that connect the city’s downtown subway stations with a series of malls, office buildings and universities are more a convenient way of getting around than a noteworthy destination in itself” (Staff 2016).

Discussion: A Hidden Contract

To summarize, Montreal’s RÉSO is well-liked, and despite the controversy, “Minneapolis’s Skyways aren’t going anywhere,” or so reads the headline of a 2016 StarTribune article (Editorial Board, 2016). With controversy in Minneapolis and contentment in Montreal, it is important to consider what each city really paid for their privately funded GSPS, and if they either won’t or shouldn’t go away, how municipalities can leverage their existence to provide public amenities to city residents.

Quasi-public spaces and “private patronage”

The sleek wooden steps overlooking the Mississippi River and the city’s iconic Stone Arch Bridge wear a name tag: Bank of America City Steps. U.S. Bank Stadium is the westernmost and most recent significant addition to the Skyway System, while Target Center composes the western border. Corporate branding is an integral part of the Skyway System and Minneapolis more generally, and while mere names aren’t everything, they do imply, if not a greater reliance on private funding for public amenities, then certainly a greater degree of comfort with accepting it. One scholar notes that through “generous public support and private patronage,” Minneapolis and St. Paul can host a disproportionate amount of arts centers and organizations relative to their size (Crane 2005). The Minneapolis Institute of Art, for example, which happens to be the 7th largest art museum in the U.S., is free, thanks in no small part to its corporate sponsors; the museum lists 21 companies who donated at least 50,000 USD on its website (Minneapolis Institute to Art).

The trend of appealing to the corporate class in the U.S. is not new. One 1997 newspaper clipping reported that Minneapolis was looking for a private philanthropist to support its budget-strapped library. It also reported on a proposed golf development downtown, suggesting that the Skyway was intended to cater to the tastes of wealthier suburban commuters (Flanagan 1997). Neither is this trend unique. Some of the U.S.’s most celebrated public places, such as Central Park in New York City, rely heavily on private philanthropy to pay for upkeep (Rosenzweig and Blackmar 1998). The Highline in New York, a public park in Chelsea constructed with private donations that accelerated gentrification in the surrounding neighborhood, is another popular subject of analysis for urban planners and architects grappling with these questions of public space and private dollars—a valuable good was provided at a minimal cost to city residents, but rising rents pushed many nearby residents out of their homes as a result of that technically free amenity (Loughran, 2017).

Moreover, despite the lack of new GSPS construction in North American cities, these implicit trades don’t appear to be going away. New York Department of City Planning today maintains that “Privately Owned Public Spaces,” which are quasi-public spaces constructed in exchange for floor area bonuses or waivers, are “important amenities for New Yorkers, commuters, and visitors” (NYC “Overview” n.d.). The program began in 1961, around the same time as the Skyway System and RÉSO, and there are 490 in the city today.

However, there is recent interest in making better public spaces from these deals. New standards were adopted in 2007 and 2009, likely in light of research on successful public spaces (NYC “History” n.d.). The new principles are similar to those for good GSPS: being “easily seen and understood as open to the public”—for example with clear and visible operating hours—“located at the same elevation as the sidewalk”—such as with accessible arrangement of entrances and exits—and “oriented and visually connected to the street”—like with logical spatial structure (POPS). As previously discussed, these qualities can arguably be attributed to RÉSO but are notably lacking from the Skyway. As described in the qualitative vignette, finding an entrance to the Skyway as a visitor is neither easy nor inviting, and this lack of invitation to what is ostensibly a public space is presumably even harder for people who don’t match the predominantly white office worker mold of the Skyway.

The Central Public Library

The Central Public Library in Minneapolis has high ceilings and fast internet. It was recently connected to the Skyway System, though I could not find the entryway, and is quite different demographically. I faced no barrier preventing me from entering the IDS center and sitting without buying anything, but I noticed a U.S. Bank Center security guard looked at me funny as I walked, admittedly in circles, through the skyways. Maybe he didn’t say anything because, besides my winter coat and camera, I fit the demographic profile of the Skyways in a way that the occupants of the Central Public Library did not. My notes from the day read “Certainly do not feel welcome here. Finding an entrance is stressful.”

Montreal's Underground City mirrors the general population to a greater extent. At the very least, one demographic group does not stick out more than the others, and the Metro’s riders are not noticeably different from RÉSO’s patrons. Its policies are less targeted as well. A 6am–1am schedule is longer, accommodates both workers with later shifts and nightlife enjoyers, and extends to the weekend and not simply the office workweek. Necessarily, the Metro entrances to the system are open during these hours, eliminating network problems caused by inconsistent policies. These policies are not just in name. RÉSO remains populated much later than Minneapolis’s skyways. There is a clear presence of poverty—which the Skyway, perhaps to its credit, displays a suspicious lack of—but it doesn’t feel unsafe. More pedestrians occupy the system for a longer period of time. As Jane Jacobs convincingly argued in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it is these populated streets that are often much safer than quiet residential neighborhoods (Jacobs 1961). Perhaps the locked, apparently pristine skyway lobbies with paid security are the North American winter city downtown equivalent.

Inflexible spaces

The extra retail space and reliance on one demographic in the Skyway may be what makes the system susceptible to criticism. It also makes it less resilient to trends in real estate. In the second quarter of 2024, Colliers reported that Minneapolis CBD had an office vacancy rate of 22.6%, while that for downtown Montreal’s was just 16.2% (Colliers MSP 2024; Colliers Montreal 2024).

Similarly, spaces designed for a specific purpose and without wider observations of the environment are susceptible to abandonment by the public. Sampson (1990) warns against such overspecialization of public spaces, noting that Victoria Square in Montreal, once a popular park, became little more than a subway stop due to “redevelopment of its edges in ways incompatible with the form of the original public space.” While the skyways have shown some multipurpose-ness—such as when around 100 protestors marched through the Skyways in protest of police violence in 2016—poor public opinion and obvious homogeneity indicates a fate similar to Victoria Square, when seen as a public space, and evidently one of failure today when seen as a profitable private project (Williams 2016). Sampson (1990) continues that public spaces should provide a relatively fixed framework to accommodate activities on a cyclical as well as spontaneous basis. The strict accordance with the work week and nonstandard hours certainly removes some of the potential spontaneity, while the cyclical absence of non-office workers again makes the space unsuited for the activities of the public of Minneapolis.

Montreal was also successful in inserting a public agenda into the private one, and the Metro was at the core of this. The city took profits from the system, and instead of using them as a tax write offs to build a large sports stadium, as was applauded in the case of Minneapolis, they built the infrastructure on which to develop a truly vibrant and sustainable city, the Metro.

Other cities and possible solutions

It could have been the influence of a visionary urban planner instead that set Montreal off on the right path. But Dallas’s GSPS was also designed by Vincent Ponte, with significant municipal support, and it was a disastrous failure (Terranova 2009). If anything, Montreal was at greater risk, with a downtown that was not emptying but already empty, with numerous vacant lots around the notorious “hole.” Montreal’s unpleasant winter climate made RÉSO fundamentally useful, but the same dynamic applies to Minneapolis. It could be different paths of Canadian U.S. cities, but the largest indoor shopping mall in North America is in Canada, not the U.S., outside of Edmonton. The differential effects of postwar trends could serve as a scapegoat, but given the geographic and cultural similarities, it is unlikely to tell the whole story. Hopkins (1996) captures familiar U.S. urbanist anxieties in a book about Canada:

The automobile, the skyscraper, the dispersed residential suburb, and the shopping mall have contributed to the demise of a pedestrian-oriented, outdoor street life in our city cores by introducing vehicular noise and air pollution, undue shade and wind, automobile dependency, and the desire, if not necessity, for pedestrian/vehicle segregation (p. 63).

Chatoney (2019) claims the two major reasons for the success of Montreal over Houston’s underground GSPS are the “number of amenities available in the respective tunnel systems” and the inclusion of public access throughout the history of the two tunnel systems (p. 2). I argue that amenities in the Skyway System are not lacking; there were several seating areas and the Government Center provided some amenities like bathrooms. Public participation would seem to indeed have an effect. In addition, or perhaps alongside the aforementioned municipal reforms, the Associated research Centers for the Underground Urban Spaces (ACUUS) was established in Montreal in 1997 to “promote partnership among all actors involved in the planning, design, construction, management and research on urban underground space” and may have a part to play in this history (Besner 2017, p. 49). While civil servants may be swayed by the tax dollars developers command, the ACUUS—which continues to publish articles about GSPS and Montreal’s Underground City—is a third party. Evidently, its interests and conclusions align much more closely with academic scholars who similarly are not swayed by money.

In addition to this source of civic and scholarly interest in the system, the critical architectural features affect accessibility. The early and inextricable integration of the Metro with the system is what made the difference.

Minneapolis is moving in the right direction in terms of expanding transit access, even with a focus on the Skyways, but its preference for a private space will not be easily changed, as can be seen by the modified ordinances in 2015. Minneapolis can thank generous private patronage for its outsized cultural institutions, but that generosity tells a choice, and it may come at a cost for residents whose presence will not contribute to the profits of developers. The characteristics of Montreal that allow for RÉSO’s success as a public space as well as a private one do not exclude Minneapolis. Rather, an ethos of private predominance in U.S. city centers like Minneapolis ignore these advantages.

If this is a solution we want to pursue, we should reconsider the terms and ask if it is worth the implicit costs, Minneapolis will not dismantle its system, but perhaps this could provide another forward push towards investment in a more robust public transportation system, for which the Twin Cities, at the same density of Montreal, are clearly suited, and which the Twin Cities seem open to supporting.

Conclusion

There is a question as to whether GSPS are even necessary. In some warmer cities, they have been dismantled. Dallas was a notorious failure (Terranova et al. 2009). Even in cold Minneapolis, residents can and do adapt. Crane (2005) argues that the extensive park network and continued application to outdoor recreation of Minnesota residents. He explains how busy streets outside of the supposedly necessary climate control of the skyway system in fact enjoy vibrant nightlife. He also argues that St. Paul’s outdoor pedestrian Seventh Street thrives at the same time as many stores migrated out of the skyway system for lack of business (Crane 2005). Similarly, the 99 Percent Invisible podcast reports “There are plenty of bustling neighborhoods in the Twin Cities known for their culture, attractions, and street life, even in the winter, proving that Minnesotans will spend time outside in cold weather if given the chance” (Thornton 2021).

Skyways and underground tunnels can be nice, improving the quality of life for a city’s residents. They can be even nicer when they are privately funded. However, when cities accept such gifts—weather protection and the occasional lobby (or rather, when we facilitate their giving through a lack of policy and soft amendment of codes)—what really are they giving up? If this new space is not fought for by the municipality and the public, and if it becomes a substitute instead of a complement for true public spaces, such free gifts may harm a city. Likely, it disadvantages certain people more than others. In Minneapolis, office workers get the full benefit of a climate controlled workday. They can drive into the city in their heated personal vehicle, park in one of many parking garages built with tax dollars, walk to their office and work in their job, enjoy a coffee or a meal on their lunch break, and leave. Someone living without a car in the city with less standard working hours will find this defining feature of where they live and work is locked off to them, though it dangles ostentatiously over their heads on their walk home.

Public spaces shouldn’t require paying for goods and services. In a park in the summer, someone can sit on a bench and take in the surroundings, maybe even people watch and serve inadvertently as a keeper of the peace and not pay anything for the bench or grass or air. People can enter and exit 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. The costs of a public luxury such as a GSPS are perhaps higher than a grassy park; It makes sense that they would need to be funded somehow. Indeed, the office worker in a way pays for her climate-controlled trip to work, but the downtown server does too. A few scattered lobbies with chairs and plants throughout these systems is nice, but without anyone feeling comfortable enough to use them, they may as well just be a part of the public skyscraper that paid for them. With poorly managed GSPS, we risk losing vibrant streets on the ground, a downtown that is both well served by transit, and the shops and services we need in places where we can find them.

Footnotes

[1] Hot summers and cold weather make climate control a benefit all year long, the compactness of the city center, and easier links from basements to transportation infrastructure thanks to the Metro.

Bibliography

Benson, Craig. (2024, September). Poverty in states and metropolitan areas: 2023 (ACSBR-022). U.S. Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2024/demo/acsbr-022.pdf

Besner, J. (2007). Develop the Underground Space with a Master Plan or Incentives. Underground Space.

Besner, J. (2017). Cities Think Underground – Underground space (also) for people. Procedia Engineering, 209, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.11.129

bfeils. (2024, February 15). Skyway System Bathrooms [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/Minneapolis/comments/1arvpg4/skyway_system_bathrooms/

Boisvert, M. (2007, September 10–13). Extensions of indoor walkways into the public domain – A partnership experiment. Paper presented at the 11th ACUUS Conference: Underground Space: Expanding the Frontiers, Athens, Greece. Institut d’urbanisme, Université de Montréal.

Boivin, D. J. (1991). Montreal’s underground network: A study of the downtown pedestrian system. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 6(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/0886-7798(91)90007-Q

Brunswick, M. (1997, Dec 25). New Minneapolis skyway, tunnels open. StarTribune https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/new-minneapolis-skyway-tunnels-open/docview/426917451/se-2

Byers, J. (1998a). The privatization of downtown public space: The emerging grade-separated city in North America. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 17(3), 189-205. https://doi-org.ezproxy.princeton.edu/10.1177/0739456X9801700301

Byers, John Patrick. (1998b). Breaking the ground plane: The evolution of grade-separated cities in North America. [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Minnesota].

Centraide (2024). Living in a situation of poverty. Centraide of Greater Montreal. Retrieved January 10, 2025 from https://www.centraide-mtl.org/en/living-in-a-situation-of-poverty

Central Minneapolis. (2024, April 22). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Central,_Minneapolis&oldid=1220275225

Chatoney, B. P. (2019). A tale of two tunnels: Exploring the design and cultural differences between the Houston tunnel system and RÉSO (underground city, Montreal) [Honors thesis, Texas State University]. https://digital.library.txstate.edu/

Chismar, J. (2008, Feb 07). Take the skyway...: A guide to the best lunch spots in downtown Minneapolis’s skyway system. StarTribune https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/take-skyway/docview/427949154/se-2

The City Council of the City of Minneapolis. (2015, December 15). Ordinance: Amending title 20, chapter 549 of the Minneapolis code of ordinances relating to zoning code: downtown districts and Minneapolis skyway system — standards and procedures manual.

City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development (2019, October 25). https://minneapolis2040.com/pdf/

The City of Montreal unveils Plan Montréal 2050: a guide to an even greener, safer and more inclusive city. (2024, June 11). Project Montreal. https://projetmontreal.org/en/news/la-ville-de-montreal-devoile-le-plan-montreal-2050-le-guide-vers-une-ville-encore-plus-verte-inclusive-et-securitaire

Colliers MSP Office Market Report Q2 2024. (2024). Colliers. Retrieved January 26, 2025 from https://www.colliers.com/en/research/minneapolis-st-paul/minneapolis-st-paul-office-market-report-q2-2024

Colliers Montreal Market Office MR 2024 Q2. (2024). Colliers. Retrieved January 26, 2025 from https://www.collierscanada.com/en-ca/research/montreal-office-market-report-2024-q2

Corbett, M. J., Xie, F., & Levinson, D. (2009). Evolution of the Second-Story City: The Minneapolis Skyway System. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 36(4), 711-724. https://doi-org.ezproxy.princeton.edu/10.1068/b34066System

Crane, Justin Fuller. (2005). An indoor public space for a winter city [Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Architecture]. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/31197

Cui, Jianqiang & Allan, Andrew & Lin, Dong. (2010). The development of underground pedestrian systems in city centres under the guidance of walkable cities. ATRF 2010: 33rd Australasian Transport Research Forum.

Cui, J., Allan, A., & Lin, D. (2013). The development of grade separation pedestrian system: A review. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 38, 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2013.06.004

Daniels, Eve. (2005, November). Skywalking: An inside look at the interstates of downtown Minneapolis. The Next American City. Issue 9 - Segregation & Integration. Retrieved January 25, 2025 from https://urbantoronto.ca/forum/threads/skywalking-an-inside-look-at-the-interstates-of-downtown-mi.2498/

El-Geneidy, A., Kastelberger, L., & Abdelhamid, H. T. (2011). Montréal’s Roots: Exploring the Growth of Montréal’s Indoor City. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.v4i2.176

Flanagan, Barbara. (1997, September 1). Downtown Minneapolis library needs benefactors // Check out list of recommended reading, and play gold in the skyway. StarTribune. The Flangran Memo. https://global-factiva-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/ha/default.aspx#./!?&_suid=173540180571306147692826377034

Gerdes, Cynthia, Steve Meyer & Pat Forciea (2017, May 9). Skyways or not, let’s celebrate that folks still love the magic of our downtown. Minnpost Community Voices. https://www.minnpost.com/community-voices/2017/05/skyways-or-not-let-s-celebrate-folks-still-love-magic-our-downtown/

Hopkins, Jeffrey. (1996). Excavating Toronto’s Underground Streets: In Search of Equitable Rights in City Lives and City Forms (Eds. Jon Caulfield, Linda Peake) University of Toronto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt2ttmhz.9

Hungry-Attention-120. (2024, January 2). A bunch of elevators you can't access to corporate banks and such, a bunch of restaurants that are only open from 11am-130pm. [Comment on the online forum post Skyway system]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/Minneapolis/comments/18wl061/skyway_system/

Jacobs, Jane (1961). The uses of sidewalks: Safety. in The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

James Lileks (2024, January 11). Once celebrated, the skyways of Minneapolis are now being blamed for downtown's empty streets. StarTribune. https://www.startribune.com/once-celebrated-the-skyways-of-minneapolis-are-now-being-blamed-for-downtowns-empty-streets/600334258

Loughran, Kevin (2017). Parks for Profit. In Christoph Lindner & Brian Rosa (Eds.) Deconstructing the High Line: Postindustrial Urbanism and the Rise of the Elevated Park (pp. 61-73). Rutgers University Press.

The Luggage: Minneapolis Skyways. (1970, April 17). Women’s Wear Daily, 120(75), 41. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/luggage-minneapolis-skyways/docview/1862423445/se-2

Maitland, Barry. (1992, August). Hidden cities: The irresistible rise of the North American interior city. Special Series on Urban Design.

Mall of America. (2025, Jan 23). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mall_of_America&oldid=1271263596

McFarland, K. M. (2015, 09). WIRED cities: Fall into montreal. Wired, 23, 38. Retrieved from https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/wired-cities-fall-into-montreal/docview/1719270277/se-2

The Minneapolis skyway system. Skyway Access. Retrieved January 24, 2025 from https://skywayaccess.com/

Minneapolis: An Urban Planner's Guide to the City. Planetizen. Retrieved January 25, 2025 from https://www.planetizen.com/city-profile/minneapolis

Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development. (2019). Minneapolis 2040. https://minneapolis2040.com/pdf/

Minneapolis Institute of Art. (n.d.). Our Sponsors. Retrieved January 24, 2025, from https://new.artsmia.org/join-and-invest/our-supporters/

National Centers for Environmental Information. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 24, 2025 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/

NYC Planning. New York City’s privately owned public spaces. Retrieved January 25, 2025 from https://www.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/pops/pops-history.page

Ode, K. (2016, Jan 24). Walking on air: Minneapolis is a skyway city, but we know little about the system that protects us, suspends us and is growing. StarTribune. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/walking-on-air-corrected-02-03-16/docview/1759604893/se-2

Pratt, A. C. (2017). The rise of the quasi-public space and its consequences for cities and culture. Palgrave Communications, 3, Article 36. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0048-6

Rosenzweig, Roy & Elizabeth Blackmar. (1998). The park and the people: A history of Central Park. Cornell University Press.

Ratcliff, J. D. (1970). Cities of the future: Montreal's underground place ville marie provides clean, safe, weatherproof living. National Civic Review, 59(8), 426-429.

Sarnpson, Barry W. (1990). Ah Montreal! Reflections on differing views of public space, past and present. Architecture & Comportement / Architecture & Behaviour, 6(4), 293–306.

Staff. (2016). Finding art and history among the malls of Montreal's underground city. The Canadian Press. Global News. Retrieved January 26, 2025 from https://globalnews.ca/news/3121981/finding-art-and-history-among-the-malls-of-montreals-underground-city/

Statistics Canada. (2021). Table 7: Population density by proximity to downtown, census metropolitan areas, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220209/t007b-eng.htm

Terranova, C. N. (2009). Ultramodern Underground Dallas: Vincent Ponte’s Pedestrian-Way as Systematic Solution to the Declining Downtown. Urban History Review, 37(2), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.7202/029574ar

Thornton, Katie, Roman Mars (Hosts) & Rosenberg, Joe (Editor). (2021, January 26). Beneath the Skyway. [Audio podcast episode]. In 99% Invisible. Stitcher. https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/beneath-the-skyway/

Underground city (RÉSO). (2016, March 13). GO!Montreal. Retrieved January 24, 2025 from https://gotourismguides.com/montreal/underground-city-RÉSO/

Underground city, Montreal. (2024, November 30). In Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Underground_City,_Montreal&oldid=1260314910

Valendr0s. (2015, January 3). As somebody who works in Downtown Minneapolis, so would I. [Comment on the online forum post The Minneapolis Skyway System is the largest in the world covering over 69 city blocks (11 miles) which allows you to live, work, shop, dine, bar hop, attend sporting events & concerts year round; you never have to go outside, unless you want to (x-post /r/HeresAFunFact) [2272x1704]]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/InfrastructurePorn/comments/2r8s9d/the_minneapolis_skyway_system_is_the_largest_in/

Weinmann, K. (2016, Feb 24). Minneapolis skyway golf event tees off this weekend. Finance and Commerce. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/minneapolis-skyway-golf-event-tees-off-this/docview/1768755970/se-2

Williams, Brandt. (2016, April 1). Protesters rally against decision in Jamar Clark shooting. Minnesota Public Radio News. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/04/01/jamar-clark-shooting-protest-minneapolis-skyway

Your guide to the Minneapolis skyway system. Meet Minneapolis. Retrieved January 24, 2025 from https://www.minneapolis.org/map-transportation/minneapolis-skyway-guide/

Zacharias, John. (2000). Modeling Pedestrian Dynamics in Montreal's Underground City. https://doi-org.ezproxy.princeton.edu/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-947X(2000)126:5(405)