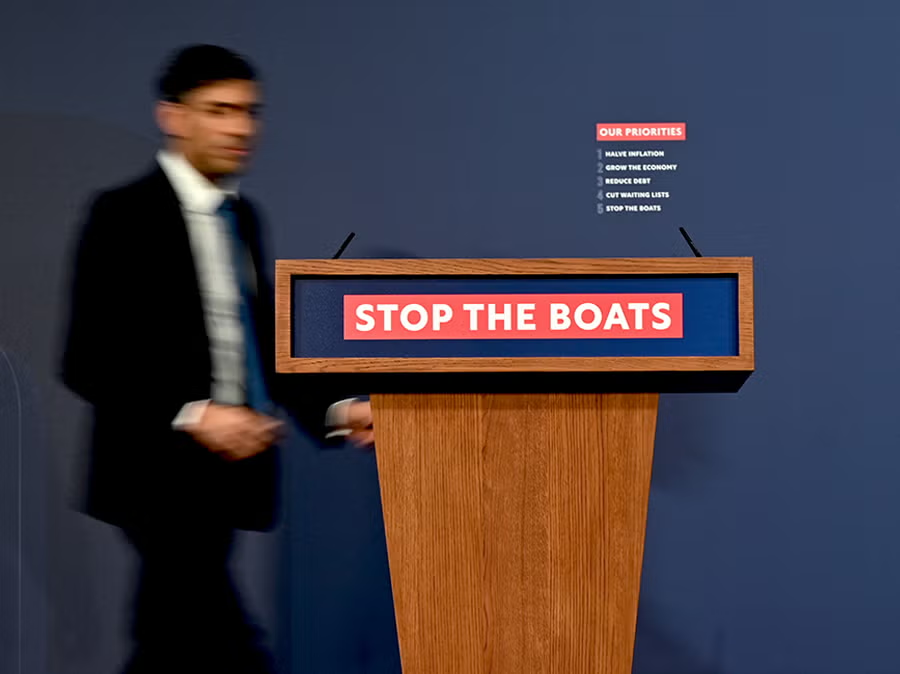

From "Stop the Boats" to "Smash the Gangs:" A Comparative Analysis of UK Public Policy on Immigration from 2022 to the Present

A comparative analysis of UK immigration policy from 2022–2025, this article reveals how both Conservative and Labour governments have embraced punitive, securitized approaches that criminalize asylum seekers under the guise of fairness and security.

Introduction

Immigration in the United Kingdom continues to be a highly divisive issue. Concern about immigration rose in 2022, and by 2024, it became the public’s “most important issue” for the first time since 2016 (Richards, Fernández-Reino, and Blinder 2025). Subsequent governments have sought to introduce policies to tackle the “global migration crisis.” In recent years, the number of people arriving irregularly through non-sanctioned means to the UK has increased sharply, largely through small boat crossings. In 2018, there were just 299 small boat arrivals compared to 45,774 in 2022 when crossings reached their height (Cuibus and Walsh 2025). Around 94% of those who arrive by small boat go on to apply for asylum. In response, government policies in the UK can be seen to have largely coalesced around preventing these irregular arrivals and, by extension, denying status to a large proportion of those who seek asylum.

The focus of this essay will be to compare government policies on immigration from 2022 to the present (time of writing, April 2025). It will compare the Conservatives’ New Plan for Immigration with Labour’s current proposed legislation. This comparative analysis shows that there is a broad continuity between the Conservative and Labour Governments’ policy and rhetoric as it relates to the criminalization of refugees and asylum seekers. Both have advanced securitized policies that position immigration as an existential threat to the nation and its safety. There are some differences in the way the Conservative and Labour governments have approached this, with some policies being more overtly justified and defended through racialized and gendered logics of understanding than others. This comparative analysis adopts an inductive approach, analysing policy documents and explanatory notes in addition to speeches and debates in parliament to draw together patterns. Mayblin (2017, 93) has identified that looking at policy documents in isolation, which are inordinately legalistic and technical, obscures the true intentions of certain migration policies. Consequently, this analysis intentionally reads policy documents in conjunction with speeches and debates to more accurately reveal the motivations that underpin them.

This essay will consist of two main sections. Firstly, outlining the previous Conservative government’s overarching New Plan for Immigration. It will focus primarily on the provisions of the 2022 Nationality and Borders Act (NABA) and the 2023 Illegal Migration Act (IMA) while referencing the UK-Rwanda Memorandum of Understanding (UK-Rwanda MoU). It will look at the intentions and justifications for these measures. This analysis will then turn to securitization theory to make sense of these findings. Secondly, this analysis will then address the new Labour government’s approach to immigration, focusing on its new piece of legislation - the 2025 Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill (BSAI) - by comparing it with the previous government’s agenda this paper reveals large similarities and, contrastingly, just a few differences.

The Conservative Government – 2022-2024

The Nationality and Borders Act (NABA) became law on the 22nd of April 2022 and is the first significant piece of legislation that acts as a vehicle for the Conservatives’ New Plan for Immigration. The explanatory notes for the Act outline NABA’s three core objectives. It aims to 1) increase the fairness of the system, 2) deter illegal entry into the United Kingdom, and 3) remove those with no right to be in the UK (UK Parliament 2021, Explanatory Notes, 4). The content of the Act, especially the provisions on asylum, has been the source of significant upset both domestically and internationally. Speaking on NABA, the UNHCR representative to the UK said that the bill would “breach international law and will cause a huge amount of personal suffering to people who are guilty of no more than seeking asylum” (Pagliuchi-Lor 2022). One core provision of the Act is that it creates a two-tier asylum system, offering differing levels of protection to refugees based on their method of travel and the timing of their claim. Section 12 of the Act differentiates refugees into two categories. A category 1 refugee must essentially “have come directly from a country or territory where their life or freedom was threatened (in the sense of Article 1 of the Refugee Convention)” (UK Parliament 2022, Nationality and Borders Act, emphasis added). Otherwise, a refugee will be considered to be in Group 2. Under section 16, those who have a ‘connection’ to any safe third country before they reach the UK may have their asylum claim deemed inadmissible. Such a “connection” is understood in very broad terms, even to those who were present and could be reasonably expected to apply for asylum in such a country. Group 2 refugee status has a series of serious practical consequences for refugees and their families. These include the imposition of harsh restrictions on accessing public funds (only available in cases of destitution) and on family reunions (UNHCR 2022). Furthermore, Clause 40 of the NABA makes “illegal entry” an explicit offense, criminalizing those who arrive in the UK without prior clearance, carrying a maximum penalty of 4 years imprisonment (UK Parliament 2022, Nationality and Borders Act).

The criminalization of seeking asylum and the cruel stratification of refugees runs in contravention of Article 31(1) of the 1951 Refugee Convention which states that “the Contracting States shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence, on refugees who, coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened in the sense of article 1, enter or are present in their territory without authorization…” (United Nations 1951). The Conservative government has homed in on the phrase “coming directly” to defend its policy, arguing that if refugees pass through safe countries such as France, then they do not come directly from where they face persecution. Therefore, in the eyes of the Tory government, the differentiation and criminalization of refugees can be justified and seen as consistent with the Refugee Convention. This interpretation has been debunked as a gross and fundamental misapplication of Article 31(1), which was intended to prevent those already lawfully settled with secured protection from continuing irregularly (UNHCR 2022, 9). Yet, conservative politicians have not shied away from this element of the NABA; rather, they have brought it to the fore and championed the visionary policy for its innovation. Speaking on the Bill, then-Home Secretary Priti Patel proudly proclaimed that “for the first time, how somebody arrives in the United Kingdom will impact on how their asylum claim is processed.” (Patel 2021).

Confusingly, the Conservative government has continually framed the differential treatment of refugees, stripping them of their protected rights and their criminalization in the language of “fairness”. For instance, then Prime Minister Boris Johnson spoke about the “rank unfairness” of the previous asylum system (Johnson 2022). Central to the rhetoric on NABA is an envisioned “firm but fair” asylum plan, based upon the supposed commonsensical separation of genuine/bogus and legal/illegal asylum seekers. Asylum seekers who arrive via irregular means were widely described in parliament as “queue-jumpers” hell-bent on gaming the system. In the second reading of the bill, the comments of Conservative MP Jane Stevenson reflected this: “we should all want a fair and just asylum system, and such a system does not say if you are young enough, fit enough or brave enough they can get ahead and jump the queue.” (UK Parliament 2021, House of Commons Debates). Crucially, the government posits that by making the system more “fair” through NABA, there would be more resources to help “genuine” refugees, those most in need, who arrive through safe and legal routes. The then Home Secretary echoed this, stating, “in standing by the world’s most vulnerable, we will prioritise those who play by our rules, over those who seek to take our country for a ride” (Patel 2021).

These ideas were further strengthened by Suella Braverman during her tenure as Home Secretary, who presided over much of the UK-Rwanda MoU and the 2023 IMA. Building and escalating the provisions of the NABA, the 2023 IMA creates what effectively constitutes an “asylum ban” (UNHCR 2023). While the NABA implemented a discriminatory two-tier asylum system, the IMA states that anyone who arrives by irregular means will not be able to have their asylum processed in the UK at all. Clause 2 outlines that the Home Secretary must remove any person who has not been granted prior leave to enter the UK (UK Parliament 2023, Illegal Migration Act). Effectively, subjecting asylum seekers who have undertaken perilous journeys to indefinite detention until they can be removed to a third country, such as Rwanda. This is true regardless of the merits of the claim, outlined in Clause 5, which allows for the disregard of protection even despite a human rights or modern slavery claim. (UK Parliament 2023, Illegal Migration Act). Such provisions were continually justified as the height of fairness and even of compassion. As the law escalated, so did the rhetoric; increasingly under Braverman, migration was portrayed through a lens of unfairness: the “broken” asylum system constituted a moral imperative in urgent need of remedy. Thusly, the Conservatives have used “fairness” as a rhetorical device in three main ways.

The first and most common use is that the small boats crisis has been deemed unfair to the British people. Invoking the will of the British people is a particularly emotive tactic that politicians like to use to push through their legislative agenda, to deflect scrutiny and criticism. In the past, politicians used emotive rhetoric of this kind frequently during debates on Brexit (Merrick 2016). The Tories have similarly used this type of language to push their New Plan for Immigration: “for a Government not to respond to the waves of illegal migrants breaching our borders would be to betray the will of the people we were elected to serve.” (UK Parliament 2023, House of Commons Debates). The British people have been continually characterised as ‘generous and compassionate’ when it comes to accommodating those fleeing persecution (UK Parliament 2021, House of Commons Debates). However, some MPs have argued that the increase in irregular asylum seekers has been said to have tested the limits of the British people a step too far – “their patience has run out” (UK Parliament 2023, House of Commons Debates). Furthermore, the failure to stop these arrivals would be unfair and unsafe for the British people. In the discussions on the NABA and the IMA, politicians frequently spoke about the presence of asylum seekers as a fundamental threat to the integrity of Britain’s borders, people, and communities. Time in the chamber that could have been spent discussing the intricacies of asylum legislation was rather used to peddle harmful rhetoric, obfuscating the conversation by conflating foreign national offenders, murderers, and rapists with those seeking refuge and fleeing persecution. For example, during the second reading of the NABA, Patel forwent a compassionate tone for those who embark on such perilous journeys across the channel; yet it took her less than a minute to mention the “murderers, rapists and dangerous criminals” who are trying to breach our shores (UK Parliament 2021, House of Commons Debates).

Secondly, it is argued that to retain the asylum system in its current form, in which people are subject to exploitation by smuggling gangs, is unfair to those who attempt to cross the channel. MPs have highlighted that smuggling gangs exploit people’s hope: “people get seduced by the fantasy that if they get here, the streets will be paved with gold…they are the victims of crime” (UK Parliament 2021, House of Commons Debates). By removing the incentive for asylum seekers to come, so the Tories argue, the model of people smugglers is disrupted, and vulnerable people are no longer subjected to their exploitation. Johnson has utilised this humanitarian logic, stating that, “there is no humanity or compassion in allowing desperate and innocent people to have their dreams of a better life exploited by ruthless gangs, as they are taken to their deaths in unseaworthy boats.” (Johnson 2022). In this way, the Conservatives take the exploitation that asylum seekers face and use it as a device against them; they purport that removing their enshrined rights and protections is fair, just, and compassionate because it supposedly breaks smuggling networks and prevents further misery. This is simply wrong, as it attacks the extreme measures refugees take to escape harmful circumstances without addressing the underlying impetus of migration itself. Inverting their desperation as a tool to attack immigration cuts off further discussion to ameliorate refugee infrastructure, the creation of safe and legal routes, or even providing for supportive international policy to buttress exploitative groups from taking advantage of asylees.

Thirdly, it has been claimed that to let the boats continue to cross is unfair to “legal” and “genuine” asylum seekers. It has regularly been declared that the UK’s asylum system is “broken” and, as a result, our capacity to help people is finite (Home Office 2023). According to the Conservative government, it is irregular asylum seekers who bear the brunt of the responsibility for the system’s failings. Johnson has described asylum in the UK in zero-sum terms, “… paying people smugglers to queue jump…taking our capacity to help genuine women and child refugees” (Johnson 2022). In the eyes of the Tories, only extreme measures that include supposed deterrents, like those contained within the IMA and the UK-Rwanda MoU, can stop irregular asylum seekers. It is then – and only then – when the boats stop can the government begin to provide better support to those coming through safe and legal routes (Cecil 2023).

This analysis has established what largely comprises the Conservatives’ New Plan for Immigration and discussed some of the main discursive themes and practices that underpin it. Now, this essay will look at securitisation theory and the various ways in which it intersects with race and gender to better make sense of the more shrouded motivations of the policy agenda. Securitization, understood as being “constituted by the intersubjective establishment of an existential threat with a saliency sufficient to have a substantial political effect” (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde, 1998, 25), is a process that is essential to understanding any contemporary piece of immigration policy. Especially since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, migration has become increasingly securitized (Bourbeau 2011). Under the Conservatives’ plans, there have been clear attempts to securitize immigration, beyond the obvious criminalisation of irregular asylum seekers. When debating the NABA, Simon Fell MP vocalised the interconnectivity of migration crime with wider offences, “whether it’s money laundering, human slavery or even common scams, we must break down those silos” (UK Parliament 2021, House of Commons Debates). This clever linkage merges two nominally separate issues, projecting a perceived collective threat onto people believed to be fleeing persecution (Bonansinga and Forrest 2025, 13). In most instances, it is asylum seekers who suffer from these connections; section 15 of the IMA, for instance, allows for the seizure of the electronic devices of asylum seekers and to store their data (UK Parliament 2023, Illegal Migration Act). Some securitising attempts are more overt than others, but some of the most flagrant can be found in the House of Lords, concealed from media attention. During a second reading of NABA, Lord Hogson spoke of the “80,000 immigration offenders living among the public. That is roughly the size of the British Army”. (UK Parliament 2022, House of Lords Debates). This characterisation, an image of a mass of offenders the size and force of an Army, is a clear-as-day attempt by Hogson to present migration as an established existential threat.

A long-neglected dimension of securitization, however, is its relationship to race and colonialism. Mofette and Vadasaria (2016) argue that the securitization of migration can only be fully understood when viewed on the premise of existing racialized modes of knowing and governance. These “established grids of intelligibility” constitute a wider framework of racial governmentality which helps us to understand why securitized notions of migrants are so easily understood and diffused in threatening and violent terms (Moefette and Vadasaria2016, 293). The United Kingdom’s colonial past plays a role in the formation of these understandings. Davies et al (2021) highlight how asylum strategies in the UK must be seen in the context of colonial histories and maritime legacies. They note how the sea, and more specifically the English Channel, is highly symbolic to British Nationalism and a site in which colonial nostalgia can be articulated (Davies et al 2021, 2315). In the past, militarized narratives in the channel focused on the defence against Nazi Germany in WWII. In recent times however, it has been refugees, migrants, and the EU that have been positioned as an existential threat to British sovereignty from ‘the offshore’ following Brexit debates. It is unsurprising then, that media images of refugees approaching the shores by boat garnered such a colonial response, characterised as an ‘invasion’ by former Home Secretary Braverman (Davies et al, 2021, 2316). In this light, some of the rhetoric previously discussed takes on some new connotations. Reading between the lines, the “fairness” of the British people can be more readily seen as implying what asylum seekers are not. The “fair” British people are clearly juxtaposed with those who cheat and scrounge the system. Indeed, Bonansinga and Forrest (2025) highlight the sense of collective narcissism apparent within immigration debates in the UK, often underpinned by ideals of past-colonial greatness and the superiority of (white) British people (Bonansinga and Forest 2025, 11). In a debate on the NABA, MP Jacki Doyle-Price exhibited some of this rhetoric, “people want to come to this country because let us be frank it is the best country in the world. Why would people not want to come here?” (UK Parliament 2021, House of Commons Debates).

The Labour Government 2024-present

Now, this comparative analysis will turn to compare its findings with the current labour government’s plans for immigration. Labour’s policy agenda so far takes the form of a singular bill that’s currently making its way through parliament known as the Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill. The bill is part of Labour’s wider plan to “smash the gangs” and break down people smuggling networks. Despite promising that the BSAI would “restore order to the asylum system by putting to an end… the unworkable mess that the previous Government left us”, the contents of the Bill can be largely read as a continuation the securitisation attempts of the last conservative government (UK Parliament 2025b, House of Commons Debates). Even the name of the bill itself – the Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill – is intentional, pushing security and the top of the agenda as the foremost important element of any piece of legislation on immigration. Much of the rhetoric used by now Home Secretary Yvette Cooper plainly frames irregular migration in threatening terms as a risk to the UKs security:

Border security is fundamental to both national and economic security. Threats to the UK from serious and organised crime, including organised immigration crime, and from terrorism and hostile state actors is rapidly evolving…Small boat crossings put these threats and challenges into sharp relief. (UK Parliament 2025a, House of Commons Debates).

The provisions of the BSAI bring in new counter-terrorism style powers, with section 36 expanding the Terrorism Act 2000 allowing for DNA sampling and fingerprints to be taken from irregular arrivals at ports in Scotland, increasing surveillance (UK Parliament 2025, Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill). One of the additional, concerning elements of the Bill is the introduction of new criminal offences, outlined in chapter 2. Now, supplying or handling “articles for use in immigration crime” can land you in jail for up to 14 years under clause 13(5). Furthermore, clause 16 criminalises the collecting of information for the use in immigration crime. What exactly constitutes useful “information” for an immigration crime is not clear but left suspect and vague. Clause 16(1(a)) sets out that any information likely to be “useful for preparing for a relevant journey” could led to 5 years imprisonment. Human rights organisations and academics have rightly raised the alarm bells, indicating that these new offences will ultimately target the people seeking asylum themselves. For example, a joint brief produced by the Human for Rights network and the University of Oxford, produced deep concerns that even something as small as checking the weather on your phone could be used to build a case to convict and imprison asylum seekers (Taylor and Harris 2025). Just like their predecessors, these new offences that criminalise refugees, have been framed by their humanitarian intentions to dismantle “the most disgraceful and immoral trade in people” (UK Parliament 2025, House of Commons Deba).

The bill does have its merits. It is a welcome improvement that Labour has repealed the Rwanda-UK MoU and parts of the IMA that significantly limited legal challenges and penalised young people for refusing ‘scientific’ age assessments (RMCC 2025). However, the NABA remains intact along with section 59 of the IMA, which imposes blanket inadmissibility on refugees travelling from entire countries such as Albania. Similarly, it’s an improvement that thus far (as of April 2025), Labour has been disinclined to refer to asylum seekers as “invasions” or “swarms” or other overtly racialised language. However, this is the bare minimum. Labour’s rhetoric may not be dressed up in inflammatory language preferred by the likes of Braverman, but it is still extremely harmful. This bill was an opportunity to take a compassionate stance on immigration, to overhaul the system, and help those requiring international assistance. It was an opportunity to combat the hateful rhetoric on immigration in the UK that is especially rife in light of the Southport riots last summer. Instead, however, Labour has trudged on in the legacy of their predecessors by continuing to criminalise asylum seekers through the BSAI. However, this should not be surprising. When in opposition, Labour’s shadow Home Secretary had heaps of criticism for the government’s plans, but this criticism wasn’t primarily based on the moral failings of their legislation – it was based on cost and efficacy. Speaking in Parliament in response to Patel’s announcement of the Rwanda-UK MoU, Cooper focused her speech on the costs of the plans and the government’s failure on rates of prosecutions (UK Parliament 2022, House of Commons Debate). By adopting this counter-terror approach, its seems Labour is trying to appeal to the to more right-leaning portions of the electorate who place immigration at the top of their concerns. This is something that SNP MP Pete Wishart alluded to stating that “the bizarre videos of the Home Secretary going to deportation centres play right into Reform’s territory… All Labour is doing by going on Reform’s territory is legitimising it. You do not pander to the likes of populists… you take them on” (UK Parliament 2025b, House of Commons Debates). Indeed, this is something about which Bonansinga and Forest (2025) touch on. At the end of their article, they question whether the dynamics of populist contagion would spill over into the new Labour government.

Labour’s inability to take a strong moral stance on asylum policy has allowed some of the colonial underpinnings of migration as a racialised threat to come to the fore once again. In debate on the BSAI, Bradley Thomas MP said that:

Those who skipped the queue and arrived illegally, do not just impact us economically, but affect the social identity of our communities… there has been an increase in illegal workers in retail roles across the country, as cash-only vape shops, tanning salons, convenience stores, barbers and car washes start to litter our communities, with no social benefit to enrich our towns and villages. (UK Parliament 2025b, House of Commons Debates).

This sort of language positions migration and those who seek asylum in the UK as a fundamental threat to British values and social identity. Without Labour to take a strong stance against these types of arguments based on cultural superiority, they will continue to be peddled in the public sphere without challenge.

Conclusion

Overall, this essay analyzed the immigration policies of the Conservative and Labour governments over the past four years. It shows that there is a large continuity in the intention behind the Conservatives’ New Plan for Immigration and the Labour Party's new BSIAB. Both have a strict focus on the criminalisation of irregular asylum seekers, expanding custodial sentences, which disproportionately affect those who want to seek asylum here, not necessarily criminal gangs. Labour’s policy has a much heavier emphasis on a counter-terror approach, positioning criminal gangs as a national security threat. Yet, the contents within the BSAI reveal that it is asylum seekers themselves who are securitised. The New Plan for Immigration also had wide securitising effects; with the indefinite detention measures in the IMA, asylum seekers were treated as offenders. To legitimate conservative policies, rhetoric about the superiority of British ideals, like fairness, was frequently used. While this is somewhat more subdued under Labour thus far, the mantra of wanting an asylum system that is “fair” still remains. After 14 years of conservative rule that operated a hostile environment towards asylum seekers, it is disappointing to see this direction continuing under the current Labour government. The Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill has not been given royal assent and is still being amended. It is still unclear what harmful provisions of the bill can be removed. Labour won a landslide election last summer with a simple one-word slogan: Change. Yet, when it comes to immigration policy, Labour has failed to present anything radically different from its predecessors. This new government had an opportunity to evoke real change and offer safe and legal routes to asylum seekers. For now, however, it seems unlikely that Labour is going to divert from its highly securitised tone on asylum. If Starmer's government continues down this path, capitulating to the likes of Reform UK, they risk alienating a large proportion of their progressive voter base.

Bibliography

Bonansinga, Donatella, and Charlotte Forrest. 2025. “‘Stop the Boats’: Populist Contagion and Migration Policymaking in the UK.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, February, 1–19. doi:10.1080/01419870.2025.2465513.

Bourbeau, Philippe. 2011. Securitization of Migration : A Study of Movement and Order. London: Routledge.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap De Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Pub.

Cecil, Nicholas. 2023. “No New Safe and Legal Routes for Asylum Seekers to UK before ‘Small Boats’ Stopped, Says Minister.” Evening Standard, March 27, 2023. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/illegal-migration-bill-parliament-today-protest-rishi-sunak-suella-braverman-tory-rebellion-b1070045.html.

Cuibus, Mihnea V., and Peter W. Walsh. 2025. “Unauthorised Migration in the UK - Migration Observatory.” Migration Observatory. 2025. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/unauthorised-migration-in-the-uk/.

Davies, Thom, Arshad Isakjee, Lucy Mayblin, and Joe Turner. 2021. “Channel Crossings: Offshoring Asylum and the Afterlife of Empire in the Dover Strait.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (13): 2307–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1925320.

Home Office. 2023. Illegal Migration Bill: Overarching Factsheet. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/illegal-migration-bill-factsheets/illegal-migration-bill-overarching-factsheet

Johnson, Boris. 2022. “PM Speech on Action to Tackle Illegal Migration: 14 April 2022.” GOV.UK. April 14, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-on-action-to-tackle-illegal-migration-14-april-2022.

Mayblin, Lucy. 2017. Asylum after Empire : Colonial Legacies in the Politics of Asylum Seeking. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Merrick, Rob. 2016. “Theresa May Accuses Her Brexit Critics of ‘Frustrating the Will of the British People’.” The Independent, October 26, 2016. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/theresa-may-accuses-her-brexit-critics-of-frustrating-the-will-of-the-british-people-a7381241.html.

Moffette, David, and Shaira Vadasaria. 2016. “Uninhibited Violence: Race and the Securitization of Immigration.” Critical Studies on Security 4 (3): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2016.1256365

Pagliuchi-Lor, Rosella. 2022. “UNHCR UK Representative Rossella Pagliuchi-Lor on the Nationality and Borders Bill.” Youtube, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8TzcTiKuInk.

Patel, Priti. 2021. “Priti Patel – 2021 Speech to Conservative Party Conference – UKPOL.CO.UK.” UK POL. 2021. https://www.ukpol.co.uk/priti-patel-2021-speech-to-conservative-party-conference/.

Richards, Lindsay, Mariña Fernández-Reino, and Scott Blinder. 2025. “BRIEFING UK Public Opinion toward Immigration: Overall Attitudes and Level of Concern.” https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2025-Briefing-UK-Public-Opinion-toward-Immigration-Overall-Attitudes-and-Level-of-Concern.pdf.

RMCC. 2025. “Refugee and Migrant Children’s Consortium Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill.” https://helenbamber.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/RMCC%20Briefing_Border%20Security%2C%20Asylum%20and%20Immigration%20Bill%20Second%20Reading_TO%20SHARE.pdf.

Taylor, Victoria, and Maddie Harris. 2025. “Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill: Briefing on the Expansion of Criminal Offences Relating to Irregular Arrival to the UK.” https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2025-02/border_security_asylum_and_immigration_bill._briefing_on_the_expansion_of_criminal_offences_relating_to_irregular_arrival_to_the_uk_1.pdf.

UNHCR. 2022. “UNHCR Updated Observations on the Nationality and Borders Bill, as Amended.” UNHCR UK. 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/media/unhcr-updated-observations-nationality-and-borders-bill-amended.

———. 2023. “Statement on UK Asylum Bill.” UNHCR UK. 2023. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/statement-uk-asylum-bill.

United Nations. 1951. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. Treaty no. 2545. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20189/volume-189-I-2545-English.pdf

UK Parliament. 2021. Explanatory Notes to the Nationality and Borders Act. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-02/0141/en/210141en.pdf

UK Parliament. 2021. House of Commons Debates, vol. 699, July 19. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2021-07-19/debates/FC19E458-F75D-480D-A20D-CD1E7ADC937E/NationalityAndBordersBill

UK Parliament. 2022. House of Commons Debates, vol. 712, April 19. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2022-04-19/debates/04A9FDC8-59F6-4CA9-BEBD-3B6F5850D707/GlobalMigrationChallenge

UK Parliament. 2022. House of Lords Debates, vol. 817, January 5. https://hansard.parliament.uk/lords/2022-01-05/debates/5565C246-FDC7-4A38-86E8-52825DE21125/NationalityAndBordersBill

UK Parliament. 2022. Nationality and Borders Act 2022. 2022 c.36. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/36/enacted.

UK Parliament. 2023. House of Commons Debates, vol. 729, March 7. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-03-07/debates/87B621A3-050D-4B27-A655-2EDD4AAE6481/IllegalMigrationBill

UK Parliament. 2023. Illegal Migration Act 2023. 2023 c.52. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/52/enacted.

UK Parliament. 2025a. House of Commons Debates, vol. 761, January 30. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2025-01-30/debates/25013042000016/BorderSecurityAsylumAndImmigrationBill

UK Parliament. 2025b. House of Commons Debates, vol. 762, February 10. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2025-02-10/debates/EC0D77F7-9C12-49E0-ACE8-923FCBA4BF30/BorderSecurityAsylumAndImmigrationBill

UK Parliament. 2025. Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill. HC Bill 173 (2024–25). https://bills.parliament.uk/publications/60806/documents/6505.