Experiences of the Diaspora in Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Artistic Expression

From apartheid-era collages to queer photography, Gavin Jantjes and Rotimi Fani-Kayode illuminate exile, identity, and resistance—showing how art reflects and reshapes the Black diasporic experience

Art serves as both a mirror and a window, examining issues of identity, displacement, and cultural belonging in diasporic communities. This duality is seen in comparing the work of Gavin Jantjes, a South African-born artist made famous for his work during the Apartheid government, and Rotimi Fani-Kayode, a Nigerian photographer and prominent figure in the British Black Arts Movement. Both Jantjes and Fani-Kayode encapsulate part of the Black diasporic genre which is articulated as the historical, social and cultural experience of people of African descent across centuries who have been geographically dislocated. These experiences generate feelings of exile, dissidence, displacement and resistance. This essay argues that Gavin Jantjes and Rotimi Fani-Kayode, though working in different mediums and contexts, both explored the experience of the Black diaspora by centering themes of exile, identity, and colonial legacy, offering windows into collective struggle and mirrors for personal reflection. This essay will first discuss the themes and selected works of Jantjes, then Fani-Kayode, and finally conclude with a comparative analysis of the two artists.

Gavin Jantjes

Gavin Jantjes explored the experience of the Black diaspora through motifs of displacement, belonging, and the impact of colonialism, focusing on political activist collage and printmaking. South Africa was originally founded by white settlers as the Dutch—then British—Cape Colony. In 1910 the Union of South Africa was granted independence from Great Britain and was governed by a white minority who enacted racist laws. These racist practices continued until they were formalized in 1948 when the National Party officially came into power and introduced an Apartheid state into law. Apartheid, directly translated from Afrikaans as “the state of being apart,” is a system of legalized racism in which the majority population is governed by the minority population. Jantjes was born the year the Apartheid government took power in Cape Town; he attended the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art before leaving South Africa to study in the United Kingdom.

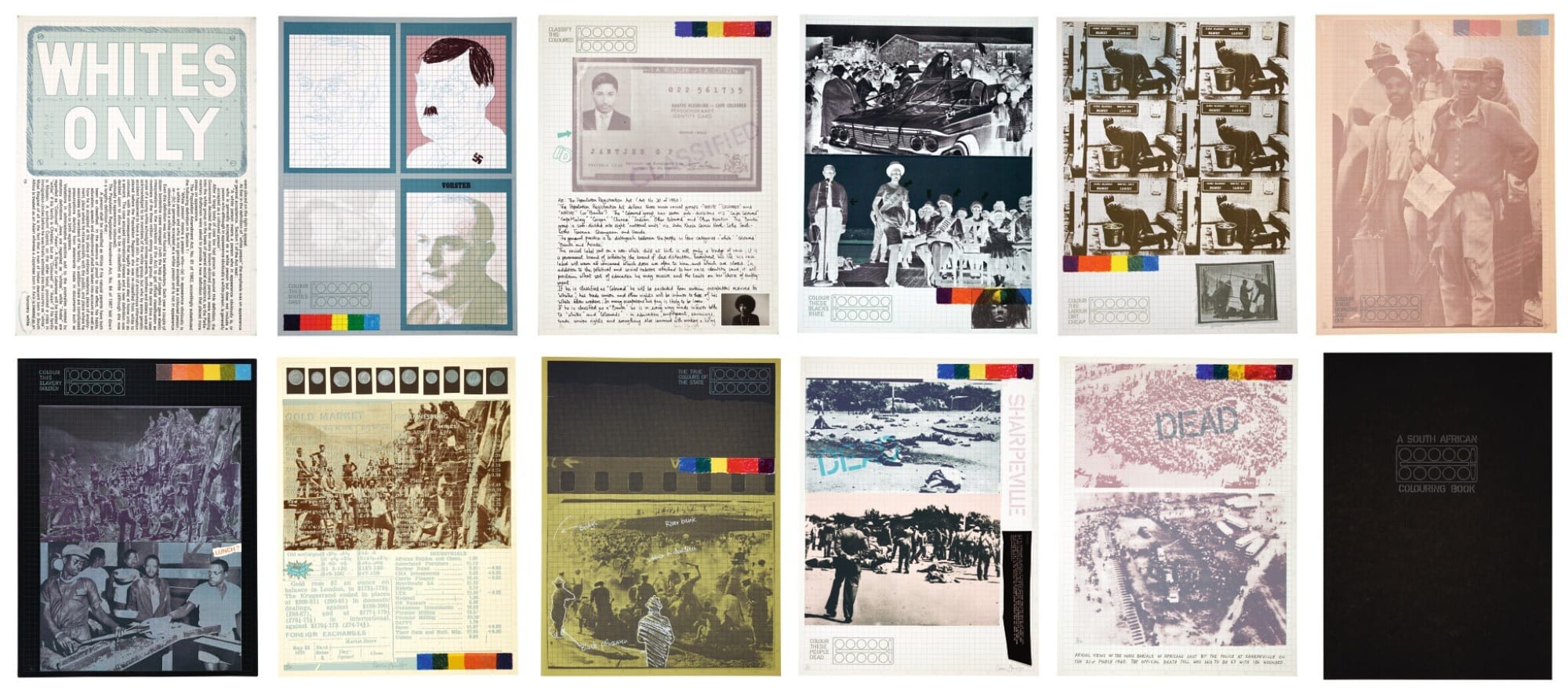

While living in London, Jantjes created art that was invested in South African liberation and echoed themes of Black consciousness through his use of popular imagery (Hill 2015, 13). Living in exile in Europe allowed Jantjes the freedom to openly critique the Apartheid regime, while also focusing on how Europe interacted with and represented Africa (Young 2017, 14). In 1973, he was granted political asylum in Germany and was shocked to find how ill-informed most Germans were about the truth of Apartheid. To educate and raise awareness, he took a playful approach and from 1974 to 1975, he created a series of works titled A South African Colouring Book (Figure 1). The title and work are intended to introduce Apartheid as if explaining it to a child and nod to the double meaning of the word as it is used by the Apartheid government as a designation of individuals of mixed-race backgrounds, such as Jantjes himself (Young 2017, 24). The work consists of pages of vivid print and colourful collages depicting scenes of everyday Black South Africans working, travelling, and living under a racist regime. The work offers a window into the long-lasting colonial legacy of the Cape Colony and its effects on the lives of Black South Africans by explicating the exploitative and extractive nature of the apartheid economy that still exists to this day.

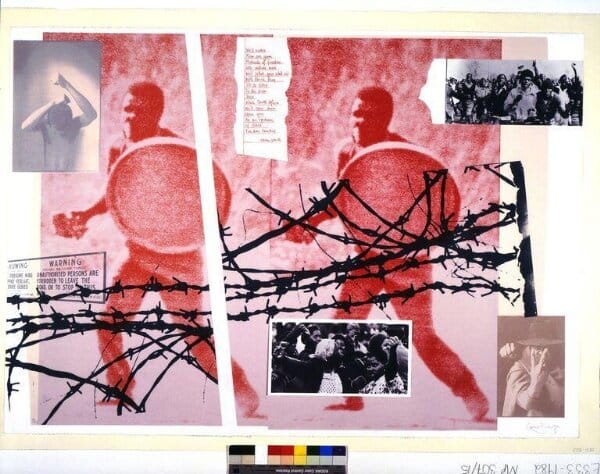

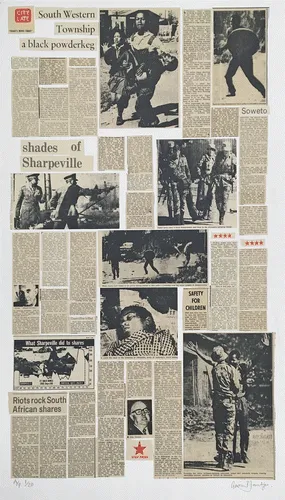

Simultaneously, Jantjes grounds his piece in human empathy, thereby making the political personal. Jantjes continued to work as a political activist, creating more windows into his experience through to the late 1970s with Freedom Hunters and City Late 26 June 1976 (Figure 2). In both works, the use of bright colors, photo-collage, and print as media underscores themes of collective oppression, colonial legacy, and identity. In Freedom Hunters, a print of a photo from the Soweto uprisings in red, along with the black barbed wire, encapsulates the violence, oppression, and resistance central to the struggle against Apartheid, evoking both the trauma and resilience of Black South Africans (Figure 3). In summary, Jantjes’s transnational identity, shaped by experiences in South Africa, the UK, and Germany, enabled him to bridge audiences, generate awareness, and foster a greater understanding of the Black diasporic struggle (Mercer 2021, 483).

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Rotimi Fani-Kayode explored the experience of the Black diaspora by engaging with questions of exile, personal and collective identity, and historical oppression, while also emphasizing his personal, spiritual, and sexual dislocation through photography. Sexual dislocation is a key theme in many of his works and is defined, in this context, as the disruption of traditional heteronormative and heterosexual social structures and relationships within a given community. Fani-Kayode was born in Lagos in 1955 and was the son of a prominent politician and Yoruba chieftain from Ife. In 1960, Nigeria gained its independence from Great Britain but subsequently fell into a civil war. Forced into exile in 1966 by the Nigerian military coup, Fani-Kayode left Lagos at age 11 to move to Brighton, England with his family (Phaidon 2021, 112). He then studied in the United States, earning an MFA from the Pratt Institute in 1983 before returning to the United Kingdom to pursue a photography career. There, he became a seminal figure of the British Black arts movement, co-founding Autograph ABP, the Association of Black Photographers (Phaidon 2021, 112). In 1999 Nigeria transitioned to a democratic federal republic, but unfortunately, Fani-Kayode was not able to see his country progress as he died at the age of 34 in 1989, during the height of the AIDS epidemic.

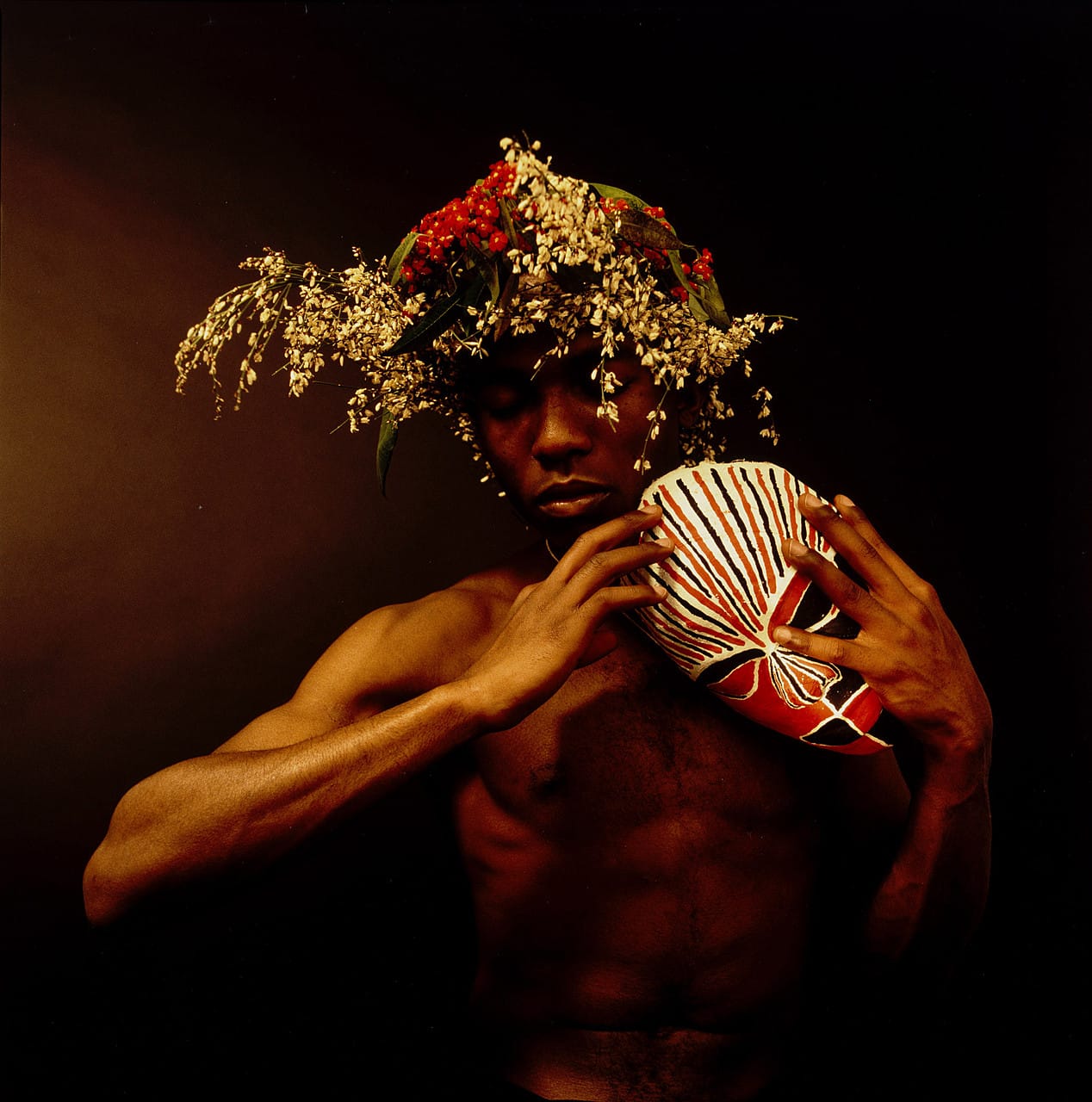

His personal experience with sexual dislocation as a queer black man in a diasporic setting is illustrated through his use of composition and colour, as seen in works such as Adebiyi (Figure 4). In this photograph, he positions a male figure in a traditionally feminine pose, challenging cisnormative ideas while also celebrating and normalizing queer love. Here queerness, understood as a sexual or gender orientation that does not align with the established idea of heterosexuality or cisgender identity, becomes a subject of Fani-Kayode's photography that allows him to reimagine identity, desire, and belonging in a way that resisted normative conventions of the time. This choice epitomizes the theme of sexual dislocation seen across his other photographs and served as an inspiration for other queer black photographers, including Zanele Muholi in their series Faces and Phases (Figure 5). The piece also touches on Fani-Kayode’s Yoruba heritage as the mask depicts the stripes of Eshu, the trickster God of Yoruba Mythology. Fani-Kayode was frequently influenced by his Yoruba heritage, routinely subverting symbols associated with homosexuality and spirituality, diaspora and desire (Phaidon 2021, 112).

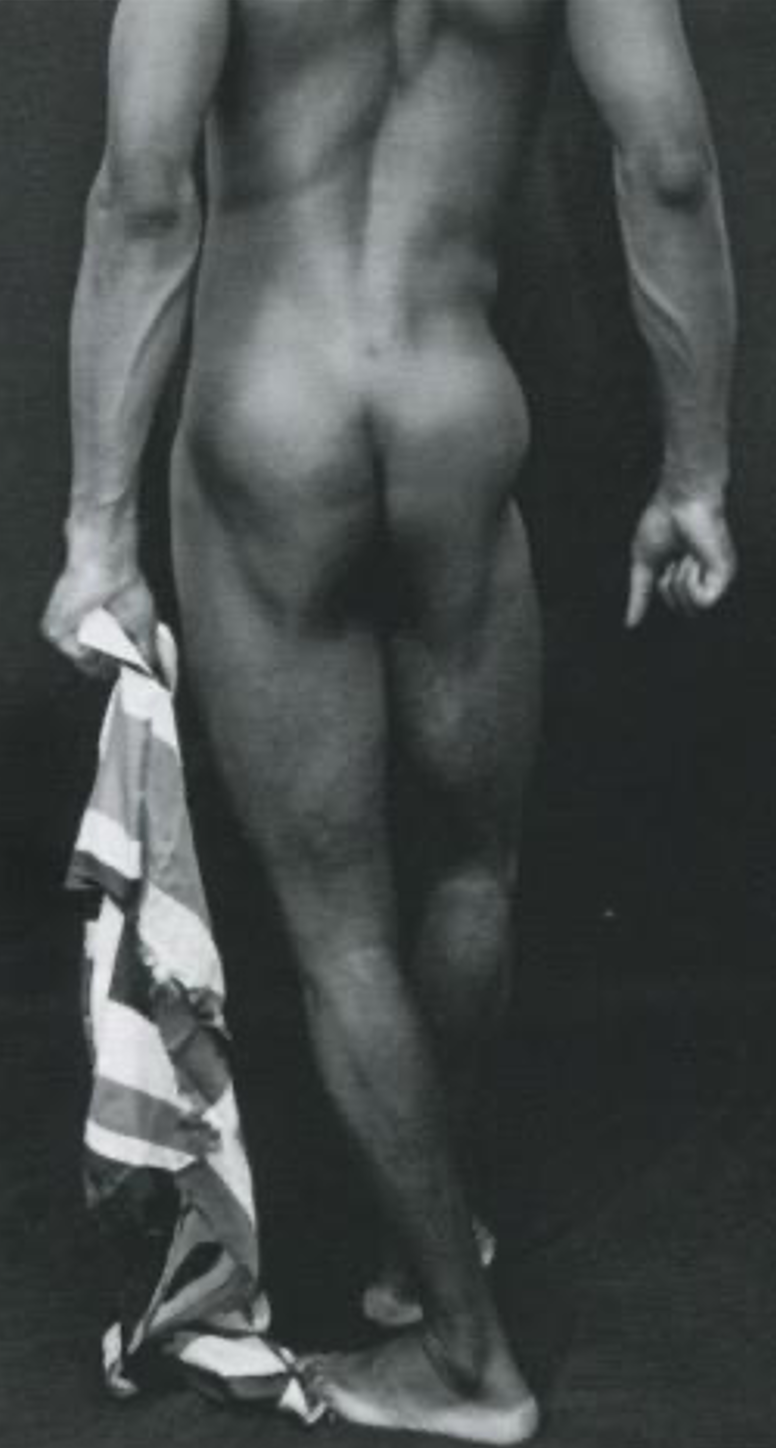

Another of Fani-Kayode’s photos that touches on queerness and the legacy of British colonialism in Nigeria is Union Jack (Figure 6). The piece shows the back of a man standing at attention holding a limp Union Jack in his left hand. Fani-Kayode’s employment of chiaroscuro and composition of figures highlights the notion of nude and nakedness as it concerns the black male body, with all its homoerotic inferences (Enwezor 2009, 217-8). The visual comparison of a strong black queer man standing at attention next to a deflated Union Jack flag, a symbol of a colonial powerhouse, demonstrates how Fani-Kayode centralizes what is relegated to the periphery and peripheries what is central. This act of visual reclamation transforms the Union Jack from a symbol of oppression into one of resistance and self-definition. This transformation parallels the switch of the feminine and masculine in Adebiyi and shows black reclamation and kinship as a focus in the Black diasporic community. With his photographs, Rotimi Fani-Kayode builds mirrors into his world and allows others who feel the same to see themselves, their struggles, and their communities directly reflected in art.

As seen through the comparison of Jantjes and Fani-Kayode’s works, diasporic identity manifests in both public and personal realms. Each approach has a different objective but is equally as important as the other. Firstly, their contrasting use of artistic medium sets a clear tone about their objectives. Jantjes printmaking, with its bold colour and reproducibility channels urgency and mass protest; Fani-Kayode’s intimate photographs invite personal contemplation and reflection. Secondly, as previously mentioned, the concept of building windows and mirrors is essential in understanding both artists’ works. Jantjes’s goal of political activism and truth-building compels him to create windows connecting the European world to South Africa. His target audience is those who do not know what it is like to be part of the Black diasporic community. His work can be read as a call to action and empathy. In contrast, Fani-Kayode’s photographs act as a mirror of his personal experience and expression. His work primarily addresses members of the diasporic community, and his work is community-enforcing and uplifting, assuring that the Black queer diasporic community does not go unnoticed.

In summary, both Gavin Jantjes and Rotimi Fani-Kayode examined the Black diasporic experience through themes of exile, identity, and colonial legacy. Jantjes approached these issues through politically charged collage and printmaking that addressed collective oppression in South Africa as seen in A South African Colouring Book, Freedom Hunters, and City Late 26 June 1976. Fani-Kayode expressed similar themes through photography, focusing on light and composition to illustrate his personal, spiritual, and sexual displacement. Separately, each artist creates a unique space specific to their target audience in which they can foster connection, empathy, and representation. Together, their works demonstrate that the Black diasporic experience is not defined by one story but rather is weaved together by complex histories and individual experiences.

Bibliography

Enwezor, Okwui. 2009. “The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition.” In Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity, by Geeta Kapur, Rosalind Krauss and Antonio Negri, 207-235. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hall, Stuart. 2006. “Black Diaspora Artists in Britain: Three ‘Moments’ in Post-War History.” History Workshop Journal (61): 1-24.

Hill, Shannen L. 2015. “Shaping Modern Black Culture in the 1970s.” In Biko's Ghost: The Iconography of Black Consciousness, by Shannen L. Hill, 1-46. University of Minnesota Press.

Mercer, Kobena. 2021. “The Longest Journey: Black Diaspora Artists in Britain.” Art History 44 (3): 482-505.

Phaidon Editors. 2021. African Artists: From 1882 to Now. Phaidon Press.

Young, Allison K. 2017. “Visualizing Apartheid Abroad: Gavin Jantjes's Screenprints of the 1970s.” Art Journal 76 (3-4): 10-31.