Communication is Key: Instituting Reform in New York’s IDNYC-Mayoral Partnership for Immigrant New York

This paper analyzes NYC’s IDNYC-MOIA partnership through a principal-agent lens, revealing inefficiencies and proposing reforms—like increased communication and agency consolidation—to better serve immigrant communities.

Introduction

Despite popular belief otherwise, the New York Mayor’s Office offers critical resources to city locals outside of the political controversy in the Adams administration interfering. One of the most critical resources within its inventory is the IDNYC program, a city identification program that allows locals of multiple backgrounds, citizenship statuses, and economic strata to take advantage of numerous benefits usually not available to the public. These benefits include discounted subway fare cards, reduced prices for fitness memberships, and free access to over a dozen New York Museums (“Benefits - IDNYC,” n.d.). The chief reason why this program is so widespread and popular is because it offers these benefits to locals who may not identify as US citizens. City residents who are undocumented, paroled on humanitarian exemptions, or protected under temporary status are allowed to seek these benefits if they can provide the appropriate documents to demonstrate eligibility. More interestingly, many of these non-citizens seek the IDNYC not for the substantial lifestyle benefits it offers. The mere fact of having another official ID is incentive enough for thousands of people to apply for these cards annually. The Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA) recorded 3,051 IDNYC enrollments during the 2023 annual year (Adams and Castro 2023).

However, like any city program, the IDNYC and MOIA partnership is subject to several constraints and operational issues that can be classified as principal-agent problems. Principal-agent dynamics describe generally the relationship between stakeholders and constituents. It usually describes a relationship where one party (the principal) delegates tasks or decision-making to another (the agent), whose interests may not always align with the principal’s goals. For one, the IDNYC contains high-powered incentives for the locals to apply and receive one. MOIA personnel who use language resources, outreach, and local nonprofits to help petitioners write an application are incentivized to enroll people in the IDNYC program because their office’s funding is often allocated based on positive metrics they can cite as they tracking their IDNYC engagements. But whether an applicant successfully receives an IDNYC after they apply carries no cost or incentive on the department that issues them. The IDNYC office experiences no costs or positive payoffs linked to their enrollment numbers; beyond salaries, no incentive schedule exists to motivate them to enroll people in their program. This poses a unique challenge for MOIA, the IDNYC office, and New York Locals who are forced to navigate an increasingly tumultuous immigration landscape where an IDNYC could make all the difference.

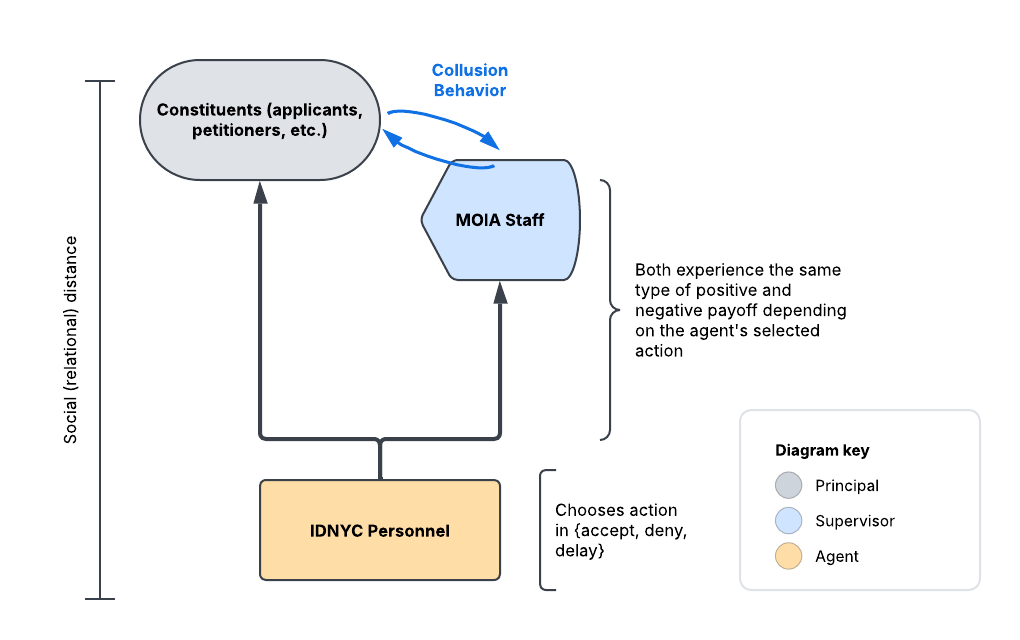

By examining the dynamics of the IDNYC program using applicants as principals, MOIA personnel as supervisors, and IDNYC office administrators as agents, this paper argues that a collusion framework is aptly positioned to describe the three-party, moral hazard, and adverse selection apparatuses at work in this case study. Further, this framework offers reform to increase IDNYC-MOIA communication and even support MOIA’s transformation into a city agency to consolidate the program into a single operational entity, despite limitations. This paper is organized in a stepwise format whereby each section builds on the last to formulate the central thesis above. The first section covers the background of the IDNYC-MOIA partnership and the program itself with an attention to issues the initiative faces. The second aligns the background with existing literature about principal-agent problems, moral hazard, and adverse selection to build a framework around collusion. The third section addresses reform to the status quo while the final portion of the paper synthesizes these findings and provides a final impact statement on the value of this analysis.

Background

Using the author’s work at MOIA as an evidentiary impetus, examining the inner workings of MOIA and their IDNYC partnership exposes several problems that can be characterized through principal-agent dynamics. This section outlines first the work of MOIA, shifts to discussing their IDNYC program partnership, and outlines existing issues in the initiative with special attention to the “ideal world” of this program.

MOIA is one of the most important city offices in charge of looking after immigrant communities across all five boroughs of New York City. Their charter-mandated duties include “advising and assisting the mayor, council, and other agencies” on programs that impact immigrant New Yorkers. They are responsible for monitoring state and federal policies while increasing access to city programs and benefits that impact immigrants. Part of their work includes helping “advise on the legal services of immigrants” and involves collaborating with other agencies to issue “U visa and T visa” declarations (“About - MOIA,” n.d.). As evidenced above, the work of MOIA is multifaceted. The office engages multiple workflows to achieve all the various goals outlined in its charter. The IDNYC initiative is a critical program for MOIA not just because it fills some of the goals mentioned above, but because it provides numbers to determine how successfully those goals—and therefore their charter—is met. For instance, MOIA began publishing their work with the IDNYC program as early as 2015 and documented over 800,000 cumulative enrollments between the first quarter of 2015 and second quarter of 2016 (Daley et al. 2016). This speaks to the early successes of the INDYC program at first glance.

The INDYC program is complex, but several important details are worthy of note before unpacking its problems. During fieldwork, MOIA personnel engage with immigrant communities around the city and offer to sign up constituents for the IDNYC program. They check documents, answer questions, and help prepare prospective applicants for their registration appointments at IDNYC offices around the city. Often, MOIA liaisons record the personal information of prospective applicants and book appointments on their behalf when open times are released on the IDNYC website at the end of the work week. This allows MOIA personnel to eliminate potential barriers for applicants who may not be technologically savvy or proficient in English and assist people unable to book an appointment independently. Once an appointment is set by a MOIA liaison, the process and outcome are determined by a constituent; individuals are responsible for showing up to their appointments on time with the appropriate documents to acquire an IDNYC. Applicants receive their IDNYC or a notice of denial three weeks after their application is submitted in person. During this time, the MOIA Constituency Services (CS) team follows up with applicants to assess the outcome of their appointment. In many cases, these follow-up calls return positive results (i.e. the constituent received their IDNYC after waiting the required three weeks) and no further action is needed. Unanswered calls, indeterminant outcomes, and special circumstances require additional engagement by MOIA staff. Many times, MOIA personnel will have to correct applications, help applicants find additional supporting documentation, or restart the IDNYC application process.

This overview of the IDNYC-MOIA collaboration hopefully illustrates a few key issues in the program. Application decisions are meted out by the IDNYC office while MOIA personnel are required to re-engage with petitioners to correct unsuccessful attempts. This means that application preparation, decision-making, and follow-ups are carried out by MOIA staff members without the collaboration or oversight of the IDNYC office. Thusly, previewing some of the principle-agent language of this paper’s next section, incentives to grant applications fall squarely on MOIA staff while adverse selection and costly vetting rests with the IDNYC office. This is compounded by the fact that MOIA liaisons and CS team members rarely—if ever—engage with IDNYC personnel to help constituents apply for the program. Each office is siloed aside from the sporadic meetings between high-level MOIA commissioners and the IDNYC program director. This disjunction creates an incredibly challenging work environment for the IDNYC program and invites avenues for reform. Key among these visions for reform is the consolidation of the program within a single Immigrant Affairs Agency (IAA) at the city level that can assist, decide, and follow up with IDNYC petitioners in a single, streamlined workflow. Other reforms presented, however, are more realistic. To bring these reforms to a point, the next section of this case study translates this background into the language of principal-agent theory, moral hazard, and adverse selection with specific emphasis on the collusion framework developed by Jean Tirole.

Principals, Agents, and the Collusion Framework

The overarching issues within the IDNYC program and its MOIA collaboration can be described using a collusion framework and the dual theories of moral hazard and adverse selection that describe the problems at hand. This section begins with a description of principals, agents, and the collusion framework before applying moral hazard and adverse selection theories to the case study. Following, the idea of collusion is re-introduced to show how information sharing can reduce the impact of costly payoffs for supervisors and agents.

Broadly speaking, the principals in this case study are IDNYC petitioners. The actions of agents (IDNYC personnel) can carry either costly harms or high-powered incentives for principals. In that sense, the actions of city personnel have a direct and somewhat measurable effect on the payoff of a principal (applicant) in this case study (Dixit 2002). The sheer number of yearly applicants for the IDNYC program also means that this case study deals with multiple principals with—for simplicity’s sake—nearly identical demands and desired payoffs.[1] The agents in this instance require a bit more explanation. IDNYC personnel are most aptly described as agents because their behaviors and actions impact directly the principals’ payoffs. They can pick from a suite of two, sometimes three actions (outright accept, outright deny, or deliberate/delay a decision about an application) that directly influence the type of payoffs observed by the principal. Extending Tirole’s model of collusion further, MOIA personnel can be categorized as supervisors. These supervisors lack the time and resources required to “run the vertical structure” of something like the IDNYC program, where running the appointments, conducting vetting, and issuing decisions are taken on by IDNYC personnel rather than MOIA staff (Tirole 1986, 183). Thus the three-tiered structure (Figure 1) emerges: IDNYC personnel are agents who pick “a productive action affecting the principal,” MOIA staff are supervisors, and applicants are principals who observe payoffs.[2] Each action of an agent has a direct and measurable impact on whether the principal gets an IDNYC and receives a positive payoff (the IDNYC card and its benefits) or a negative cost (additional time to file another application or other personal inconveniences). This discussion of principals, agents, and supervisors yields to an important consideration of moral hazard and adverse selection that play into this case study.

Firstly, the question of moral hazard and incentives is key to address. For one, the IDNYC program is free, and while principals must pay for a replacement ID, they need not pay to apply at first. This helps the program remain open to individuals of all socioeconomic backgrounds for whom payment might pose a barrier of entry into the IDNYC program. But this also means that there is no incentive scheme at work to motivate the actions of agents (Dixit 2002). Agents are paid a fixed salary to make decisions that impact principals and there are no incentives at play to allow principals to push agents towards a particular action and outcome. Interestingly, supervisors—MOIA personnel—do see payoffs associated with their actions in a similar way as principals. If principals receive a positive payoff, the supervisor’s work is rewarded by non-monetary, morale incentives that boost their on-the-job satisfaction. Principals who receive the IDNYC get dual payoffs of having an official ID card from the city and the numerous lifestyle benefits of the IDNYC program. If supervisors know about these positive payoffs seen by the principals, they receive a portion of those payoffs via morale. If principals do not get an IDNYC, MOIA staff and principals incur costly payoffs. Both must (1) spend extra time to review the application, (2) submit another paper form, and (3) make time to schedule and attend an appointment at an IDNYC office. Thus, it is easy how the theory of moral hazard and incentives affect the IDNYC program; the central dilemmas are outlined for ease of access below:

1. Agents choose from a menu of two, sometimes three options (accept or deny—or even delay—the principal’s application) that influence the payoffs of the principal.

2. There is no incentive schedule at play to influence the decision of agents towards the desired outcome of the principal.

3. Principals incur positive or negative payoffs depending on the decision of the agent. They receive positive payoffs if their application is accepted and negative payoffs if denied.

4. Supervisors incur payoffs based on the actions of agents commensurate with the payoffs observed by principals.

The question of adverse selection discussed next is chiefly what generates the exigent collusion and information sharing between principals and supervisors to limit the actions of the agent.

In the case of IDNYC applications, the relevancy of adverse selection appears differently than proposed in the literature about incentives for information. Typically, the principal is trying to determine the type of the agent; in this case it is the reverse. IDNYC personnel (agents) try to determine, through a slew of vetting measures and document requirements, whether the principal qualifies for an ID card. Over the course of many years, the IDNYC office grew the number of requirements for applicants quite substantially. Currently, the IDNYC online “Document Calculator” provides an exhaustive way for principals to determine—measured using a point system—whether they qualify for an IDNYC in the first place (“Document Calculator - How to Apply - IDNYC,” n.d.). These documents require the principal to do more work prior to when the agent must make a decision that informs the character of the principal’s payoffs. It also means that agents are responsible for determining the type of the principal, rather than the other way around. Even though the literature argues that principals are often required to design a “mechanism to elicit the truth,” this case study provides an alternate scenario (Dixit 2002, 700). Agents must use a standard operating procedure (the “Document Calculator,” in a way) and in-person session to determine the type of the principal and whether they qualify for the IDNYC and its benefits. If the agent issues a denial, then costly vetting falls on both the principal and supervisor to pursue. Both the applicant and MOIA personnel—tasked with assisting—will incur the bulk of the time and resource costs to review the application and reapply for the IDNYC program. As a result, the agent should, in theory, deliver the outcome that they like the least (i.e. universal acceptances) if they want to avoid the principal’s reapplication or an audit by MOIA leadership.[3] This is where Tirole’s mechanism of collusion factors in most heavily and builds on this slightly nuanced “twist” in conventional understandings about adverse selection prerequisites and the mechanisms of costly verification.

To (1) limit the available choices of the agent, (2) avoid inducing a costly audit or verification of the agent’s actions, and (3) increase the likelihood of desirable payoffs, supervisors and principals—rather than supervisors and agents—will collude through coalitions and covert transfers. For the purposes of this analysis, monetary transfers are not considered part of this collusion framework because the there are no fees required to submit an IDNYC application for the first time (Tirole 1986, 186). The manipulation of information received by the agent—rather than principal—is more applicable instead. Information manipulation by the supervisor and principal is observed in the same three ways as Tirole describes: by concealing, distorting, or not creating information (Tirole 1986, 184). Seeing that the agent-dependent payoffs of supervisors and principals are linked (i.e. that supervisors and principals will either both receive negative or positive payoffs), the type of collusion relevant to this case study is one where both parties benefit (Tirole 1986, 184). The practical evidence of this information manipulation is as follows.

MOIA staff and applicants can collude and eliminate certain information on an IDNYC application. Omitting the organ donor consent in an application creates one less provision that the IDNYC staff must examine when granting an application. Even if someone wants to be an organ donor as an applicant, indicating a preference against can help advantage the application by subjecting it to review of a lesser extent.[4] Supervisors and principals can also distort information on the application form to maximize the agent’s likelihood of issuing a favorable decision with a positive payoff. For instance, if an applicant is homeless, they can conceal that information on the paper form by writing the mailing address of the shelter or temporary residence as the permanent address. This allows the agent to still grant an application even if they do not unequivocally fulfill the IDNYC’s local residency requirement. It is very hard for supervisors and principals to simply “not create” information on the IDNYC application, but in some limited cases it can be done. If applicants have both a passport and passport card, the supervisor can arrange a combination of qualifying documents that allow the principal to apply but without risking exposing more personal information than necessary (like the fact that they have a foreign electronic passport book in the first place).[5]

Tirole mostly discusses how supervisor-agent collusion mostly commonly exists, but also stipulates that other coalitions are possible if the organization’s system of informational sharing is well-understood (Tirole 1986, 200–201). This analysis shares this logic. Based on the way information moves between supervisors and principals, collusion between those groups is far more feasible than the normative supervisor-agent relationship. For instance, in the IDNYC system, the supervisor-principal coalition is most common because there is large amount of existing interaction between the supervisor and principal. This allows a coalition to be formed and covert transfers to happen laterally based on congeniality and similar, payoffs observed by the colluding parties (Tirole 1986, 196). Reforming the structure—rather than overarching goals—of the IDNYC-MOIA partnership is required to alleviate the informational manipulation that happens in supervisor-principal collusion. This requires the IDNYC-MOIA partnership to embrace collaboration and collusion-adjacent behaviors to increase efficiency. For example, more communication between players and a systematized workflow could help decouple supervisor-principal payoffs and lower the need for unsanctioned collusion. The specific nature of these reforms is addressed in greater depth in the next section of this paper.

Reform

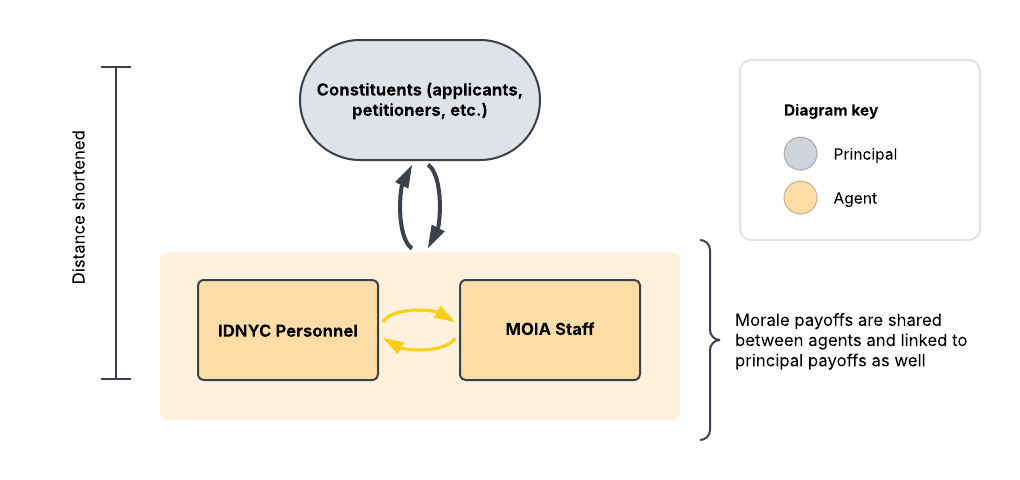

Given the issues addressed above, two recommendations (Table 1) are proposed. The first seeks greater communication between IDNYC and MOIA personnel to flatten hierarchies and redistribute payoffs. The second is more drastic: it seeks radical consolidation of IDNYC and MOIA services under a new city agency.

Table 1: Limitations and Recommendations

| Summary of Reform | Description | Limitation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Communication | Increasing communication between parties lowers the relative social distance between agents, supervisors, and principals by allowing more information exchange across the hierarchy. This allows incentives to be more reasonably distributed into the agent in addition to the principal (Figure 2). | (1) Parties must be willing and able to communicate regularly, which can be hard to induce, especially in public sector politics. |

| Single-Agency Consolidation | Consolidating all IDNYC-MOIA work into a single agency forces collaboration by designating both IDNYC and MOIA personnel as agents within a single agency, the IAA. This allows IDNYC application processing, outreach, and follow-ups to happen in a single place and delegated amongst agency staff with a single leader and mandate. | (1) Reputation: MOIA brings a lot of benefits to the mayor by reputation; the mayor is unlikely to let go of this. (2) Money: it also costs a lot of money to start a new agency, which is hard to find/provision. (3) Clash: leadership would have to be re-selected (often at the expense of existing high-level personnel). Commissioners and directors would be unlikely to give up their political influence. |

The first reform is easier to implement and has two major implications. Firstly, increasing communication between all parties reduces structural hierarchies; it forces agents and supervisors to work together for the benefit of the principal. It also allows agents and supervisors to work together, effectively turning the issue into a multiple-agent-single-principal interaction (Figure 2). Secondly, enhancing communication between all parties also allows payoffs to be redistributed; if agents know from principals the outcome of their applications, agents can experience positive morale payoffs when principals receive positive material payoffs. Integrating these communication mechanisms through a systematic workflow would solidify communication between parties as a central element of the IDNYC-MOIA partnership and carries other benefits as well. For instance, it produces an incentive schedule that will motivate agents to deliver more acceptances without necessarily compromising their vetting procedures (assuming multiple agents and redundancies help self-regulate errant acceptances). It also makes agents and principals more proximal, allowing that payoff coordination to contribute to the incentive schedule outlined above.

The second recommendation is more ambitious. It seeks to consolidate IDNYC and MOIA into a single Immigrant Affairs Agency (IAA) where supervisors and agents work together—rather than separately—to help the principal. The entire IAA staff would grant IDNYCs, relay concerns from constituents, and improve the program systematically under a single charter mandate. It reduces the problem back to a more simplified principal-agent scenario while amending some of the harmful moral hazard and adverse selection problems presented earlier. These include the nonexistent incentive schedule among IDNYC staff and costly vetting that falls mostly on principals and supervisors. While both reforms are of value, more limitations prevent this solution from being implemented. Thus, this paper favors the first reform mechanism for the following reasons (also outlined in Table 1).

The first reform has few limitations. Increasing collaboration would simply need to be mandated by the Commissioners who run MOIA and the IDNYC directors; they would need to meet more frequently depending on their availability. This is not a burdensome ask, though the reluctance of city personnel to change their practices tends to be quite difficult to overcome. Other than personnel simply not wanting to make the change, this reform has few roadblocks, all else being equal (funding, personnel numbers, etc.) The second reform carries too many limitations to be implemented but offers an ambitious solution. Consolidating MOIA and IDNYC into a single office would require large scale funding changes, new office spaces, and a new leadership structure to lead the IAA. Such changes would not be favorably accepted by either group or would such a change be positively received by the mayor who benefits from MOIA’s work by reputation. Seeing that few limitations exist in opposition to this paper’s first reform idea, readers should be optimistic that positive change can enhance the IDNYC-MOIA partnership in the future. Leadership in both groups should be open to this idea of reform not just because it is easy to implement, but because organizational theory and public sector literature support these reforms.

Conclusion and Discussion

This paper has examined the dynamics of the IDNYC program using a three-party hierarchy and collusion mechanism to explore moral hazard and adverse selection at work in the partnership between IDNYC and MOIA. It also identifies ways to reform the partnership by increasing communication to reallocate incentives and consolidating the partnership into a single agency. Despite substantial limitations on the second suggested reform, this paper contends that it would be the most effective way of enhancing the MOIA-IDNYC partnership moving forward. That means that the first recommendation, seeking increase collaboration and communication between all parties, weighs in as a modified, second-best implementation for MOIA to undertake. The reform would also produce sweeping impacts. Increase collaboration between IDNYC and MOIA personnel would eliminate the collusion activities between constituents and MOIA. This would reduce potential workplace clashes between IDNYC and MOIA personnel who are both trying to achieve conflicting goals: MOIA wants to get IDNYCs to New Yorkers and IDNYC staff want to grant IDs only to people who qualify. Communicating seamlessly and often would allow MOIA and IDNYC staff to more closely align their goals. It would better serve constituents by providing clear channels to engage with IDNYC and MOIA personnel when their applications are denied, potentially limiting negative payoffs on their end.

Informational sharing between offices would also allow MOIA staff to reach communities that might be yet unfamiliar with the IDNYC program. This would reduce the number of overlooked communities and contribute positively to the work of both the IDNYC office and MOIA. Examining communication as a key mechanism of reform should come first before weighing in on establishing a single agency. It is the easiest and least-costly solution to implement with the highest potential benefit. This paper emphatically argues that policymakers, appointees, and bureaucrats need only take the small steps outlined above enhance their work for the betterment of immigrant New York.

Footnotes

[1] This is chiefly why later diagrams—like Figures 1 and 2—use only one icon to represent a principal, versus multiple that may reflect more accurately the type of work that is going on in the IDNYC-MOIA partnership. Because priorities are nearly the same between each principal, a single icon/single principal is represented and addressed moving forward.

[2] It is worth noting that under this framework, all three of Tirole’s axioms are upheld. The third axiom arguing that the supervisor lacks the time to run the vertical structure (of the IDNYC system) holds true when MOIA’s limited staffing is considered. While many supervisors work in the MOIA office, only one team member is responsible for supervising the principal-agent interaction at a time. The second axiom holds as well: only the Deputy Commissioner at MOIA can bring concerns that principal observe to the agents at the IDNYC office. The internal hierarchy of MOIA prevents other lower-level supervisors from bringing concerns to agents. The first axiom, however, requires some expansion. The principals (applicants/petitioners) do not inherently own “the vertical structure” of the IDNYC system in the way Tirole describes. However, their tax dollars do go into the funding of the program, whereby ownership can be conceived or reasonably argued. The financial prospective applied here gives evidence of principal ownership that solidifies all three of Tirole’s axioms as relevant to this case study (Q.E.D).

[3] (Dixit 2002, 701); audits by MOIA leadership in the IDNYC office are rare but known to happen. This goes against the costly verification idea that principals and supervisors must do, per the earlier analysis in this section, but because these instances are so rare, this paper discards the relevancy of supervisor-agent audits because of how strongly (petty) personnel politics come to bear, in the author’s experience.

[4] This could mean that during an IDNYC appointment, an agent sees that the applicant selected to be an organ donor and must confirm their consent. They could reject the application if the principal lacks awareness of the organ donor program or if they change their minds, meaning they need to book a new appointment with a revised application document.

[5] This is typically harder to consider as an instance where information “may not be created” because the differences between a passport card and passport book can be very minimal in some instances. The IDNYC document guide does distinguish between an electronic passport book and a passport card and indeed gives them different “point” values for IDNYC qualification. Choosing to use the card instead of the book can be a way of protecting the passport document itself if principals are worried about losing their personal documents while they attend an appointment rather than a concerted attempt to influence an agent’s decision one way or another.

Bibliography

“About - MOIA.” n.d. Accessed March 10, 2025. https://www.nyc.gov/site/immigrants/about/about.page.

Adams, Eric L, and Manuel Castro. 2023. “2023 ANNUAL REPORT ON NEW YORK CITY’S IMMIGRANT POPULATION AND INITIATIVES OF THE OFFICE.”

“Benefits - IDNYC.” n.d. Accessed March 10, 2025. https://www.nyc.gov/site/idnyc/benefits/benefits.page.

Daley, Tamara, Laurel Lunn, Jennifer Hamilton, Bergman Artis, and Donna Tapper. 2016. “IDNYC: A TOOL OF EMPOWERMENT A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of the New York Municipal ID Program.” 1. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/idnyc/downloads/pdf/idnyc_report_full.pdf.

Dixit, Avinash. 2002. “Incentives and Organizations in the Public Sector: An Interpretative Review.” The Journal of Human Resources 37 (4): 696–727. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069614.

“Document Calculator - How to Apply - IDNYC.” n.d. Accessed March 10, 2025. https://www.nyc.gov/site/idnyc/card/documentation.page.

Tirole, J. 1986. “Hierarchies and Bureaucracies: On the Role of Collusion in Organizations.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 2 (2): 181–214.