Closing Gaps in Postpartum Care: Reinvesting in Georgia’s Maternal Mental Health Act

This policy paper explores the urgent issue of maternal mental health in Georgia, with a focus on House Bill 649 and its potential to improve outcomes for mothers experiencing Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders (PMADs).

Executive Summary

This policy paper explores the urgent issue of maternal mental health in Georgia, with a focus on House Bill 649 and its potential to improve outcomes for mothers experiencing Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders (PMADs). Georgia deals with some of the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation, with over 60% of maternal deaths deemed preventable and mental health conditions identified as a leading cause. These disparities are worsened by health inequities, limited mental health coverage, and widespread obstetric care deserts. By addressing gaps in screening and promoting community-based care, this paper outlines actionable strategies—such as expanding public awareness, strengthening the perinatal mental health taskforce, and investing in innovative healthcare delivery models like early screening and risk-monitoring systems—to support passage of House Bill 649 and ensure equitable access to mental health support for all birthing people in the state.

The Problem

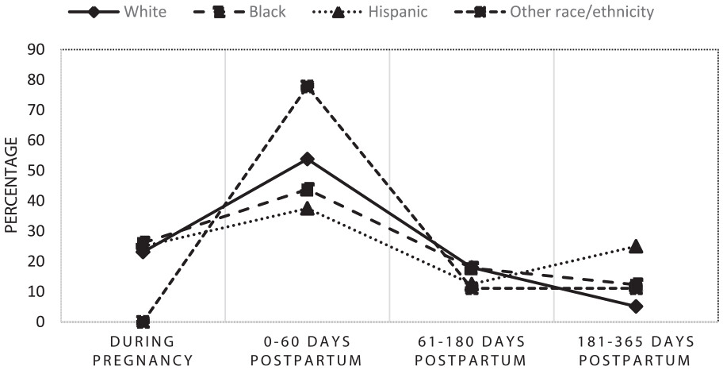

Georgia’s maternal mortality crisis is a public health emergency driven by systemic inequities, limited access to care, and untreated mental health conditions that disproportionately endanger Black women and women in rural areas. With a maternal mortality rate of 48 per 100,000 live births, Georgia ranks among the worst states for maternal health, alongside Tennessee, Louisiana, and Alabama, which also report some of the nation’s highest rate (Kondracki et al., 2024). Nationally, Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders (PMADs) are the primary complications in births, and maternal suicide is a leading cause for pregnancy-related deaths [2]. Nearly 20% of women of childbearing age in Georgia lack health insurance, and 80% of the state’s 159 counties are designated as mental health professional shortage areas, exacerbating disparities in care [4]. Together, this data highlights major gaps in Georgia’s maternal care system, where provider shortages, lack of insurance, and unmet mental health needs drive persistently high mortality rates.

These barriers fall hardest on minority women, who face compounded systemic neglect. Black women in Georgia are more than twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes, like hemorrhage, infection, and suicide or overdose, as white women, yet many of these deaths are preventable [5]. Furthermore, over half of Georgia’s rural hospitals with obstetric services have closed in the last decade, blocking essential women’s health services [4]. Despite the known risks of untreated PMADs, Georgia does not mandate universal screening, and only a select group of providers are trained to treat perinatal mental illness. Overall, limited public awareness about maternal mental health, coupled with systemic inequities—such as racial disparities in care, inadequate insurance coverage, and a shortage of mental health providers—contributes to an environment where warning signs are overlooked and care is delayed, allowing preventable maternal deaths to persist.

Proposed in February 2025, House Bill 649, the Georgia Maternal Mental Health Act, seeks to address the state’s healthcare challenges by mandating insurance coverage for maternal mental health screenings and care. Backed by bipartisan support, House Bill 649 amends Georgia’s insurance and Medicaid codes to improve maternal mental health care by mandating private and public insurance plans under Title 33 to cover comprehensive mental health screenings and care [12]. The proposed bill would require screenings for PMADs at specific points during and after pregnancy based on physician recommendations. It would also ensure people with all insurances, including Medicaid, have access to these services.

As of April 2025, House Bill 649 was withdrawn from consideration and sent back to a House committee for further review [12]. The status of the bill highlights the need for additional funding and legislative support, making it imperative that the Georgia General Assembly reassess the bill and prioritize maternal mental health initiatives. Recommitting attention and legislative bandwidth to House Bill 649 creates an opportunity to refine its strategies, and build a greater commitment toward maternal mental health across Georgia.

Recent and proposed cuts to Medicaid and Medicare further complicate its implementation, as these programs are major funders of perinatal care for low-income women. While House Bill 649 does not explicitly address federal funding reductions, it might serve to offset their impact through changes that enhance state-level infrastructure, including expanding the Perinatal Mental Health Task Force and encouraging alternative payment models sustaining maternal mental health services amid federal cuts. Altogether, House Bill 649 has the potential to change the maternal healthcare landscape in Georgia; however, due to the lack of prioritization and legislative attention, the bill remains stalled.

Proposed Solutions

House Bill 649 can significantly reduce Georgia’s maternal mortality rate by mandating comprehensive insurance coverage for mental health screenings and treatment. However, for the bill to pass, it requires support and an enhanced policy framework that addresses current challenges.

Option 1. Expand Public Awareness and Normalize PMAD Care

It is essential to broaden understanding of perinatal mental health challenges and whom they affect among policymakers, healthcare providers, and the public [3]. Maternal mental health disorders go beyond postpartum depression to include anxiety, trauma-related conditions, severe mental illness (SMI), and substance use disorders (SUDs) [12]. Focusing solely on postpartum depression can leave many unaware that their symptoms are part of a broader issue. Expanding public awareness and screening efforts to cover the full spectrum of conditions would enable more comprehensive care and earlier intervention. Advocacy groups such as Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia can play a central role in educating the public, engaging with families directly, and organizing awareness to push for policy change. However, broader mental health screening requires additional resources and trained providers, which may be difficult in areas already facing staff and funding shortages. To expand public awareness, Georgia could partner with community-based nonprofits and maternal health organizations to lead culturally tailored outreach campaigns, integrate PMAD education into existing public health initiatives, as well as collaborate with hospitals and OBGYN offices to promote statewide screening awareness. Insurance providers, including Medicaid and private insurers, must also be engaged to ensure coverage for comprehensive screenings and follow-up care. Standardizing language across agencies could promote consistency in policy and care, though coordination requires time and legislative effort.

Option 2. Strengthen Georgia’s Perinatal Mental Health Workforce

Only 8 of Georgia’s 159 counties have enough mental health professionals, and few are trained in perinatal care [4]. To address this, the state could offer loan forgiveness and tuition assistance to incentivize psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers to specialize in perinatal care—especially in rural areas with limited access. Georgia could also partner with academic institutions like Emory University, Augusta University, and the University of Georgia to develop perinatal mental health training tracks within psychiatry, nursing, and social work programs. These could be supported through state-funded scholarships or HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) workforce development grants, which have successfully expanded behavioral health training pipelines in other states. Strengthening this workforce would help ensure timely treatment for women who screen positive for PMADs. However, challenges remain, including the time required to train professionals, difficulty retaining providers in underserved areas, and potential legislative resistance to funding such programs.

Option 3. Invest in Innovative Delivery Models for Mental Health Services

Expanding telehealth and mobile maternal mental health clinics offers a viable way to bridge healthcare gaps in Georgia, especially in underserved areas. Mobile units can deliver screenings, psychiatric evaluations, and counseling to underserved communities, while expanded telehealth reimbursement would allow more pregnant and postpartum women to access care remotely, reducing barriers like transportation and childcare. Partnering with community health centers and local hospitals could help integrate virtual psychiatric consultations into routine care appointments. In 2024, CareSource launched a mobile mental health unit as part of its Wellness on Wheels (WOW) network to serve new and expecting mothers statewide [10]. To focus efforts, initial interventions could target Georgia counties with the highest maternal mortality rates and the fewest mental health providers, like in rural southwest Georgia, before scaling statewide. This approach is cost-effective compared to building new facilities and can provide near-immediate access in healthcare deserts. However, challenges such as staffing shortages and limited funding may hinder long-term success.

Georgia's maternal mortality crisis demands policy action that is sustained. Despite recent efforts through legislation like House Bill 649 and Medicaid postpartum expansion, current interventions fall short in addressing the full scope of maternal mental health challenges. Moving forward, Georgia needs to make maternal mental health a pressing public health concern, starting with the passage of the bill.

Enhancing perinatal mental health public education, investing in workforce development, and expanding access to care through telehealth and mobile clinics, along with passing House Bill 649, will strengthen Georgia’s maternal health system. Moreover, bringing these initiatives to fruition will require careful coordination across stakeholder groups and commitment to long-term funding.

Limitations

Despite persistent challenges, Georgia has a strong foundation for reforming its maternal health system through targeted, evidence-based interventions. As of now, two major efforts currently in place include the work of the Georgia Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC) and Regional Perinatal Centers (RPCs), both of which are critical yet fall short in fully addressing the mental health needs of pregnant and postpartum women.

MMRCs play a key role in investigating maternal deaths and identifying systemic failures, with reports consistently highlighting mental health conditions as major contributors to maternal mortality [5]. However, the committee lacks enforcement power, and its recommendations are not consistently adopted across hospitals. Its recent disbandment following a confidentiality breach of case review data that risked exposing identifiable patient and provider information has further limited its influence, making it difficult for advocates to gain support of its reinstitution [13].

In response to MMRC findings, Georgia expanded Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months to improve access to care, and hospitals have engaged in Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs) to enhance obstetric practices. Yet, these initiatives largely focus on physical health, with the integration of mental health services remaining an afterthought [11]. Moreover, under the current federal budget and policy climate, the proposed cuts to Medicaid funding make the sustainability of this extended coverage uncertain.

RPCs, on the other hand, function as advanced care facilities for managing high-risk pregnancies. While these centers are important in advancing physical outcomes, they often lack embedded psychiatric services or standardized mental health screening protocols. Many rural women referred to RPCs face significant transportation barriers and limited access to psychiatric care. According to a recent report, 65% of maternal deaths in Georgia involved women who had contact with a perinatal center, yet their mental health concerns went unrecognized or untreated in many cases [5]. These figures highlight a critical gap that without integrated mental health services, RPCs cannot fully address the complex needs of high-risk pregnancies.

To close these gaps, Georgia must adopt mental health as a core component of maternal care. This means strengthening MMRC’s authority by mandating implementation of its recommendations and expanding the role of RPCs to provide integrated mental health services. Additionally, the state should allocate funding for mental health provider training and loan forgiveness programs to address workforce shortages. Increasing investments in telehealth and mobile maternal health units would further bridge access gaps, particularly in underserved communities.

Moreover, the funding for House Bill 649 remains uncertain due to existing budget constraints that limit the proposed work. The bill lacks details on provisions for key locations such as rural areas, where hospital closures and transportation barriers hinder maternal care [8].

By addressing these structural weaknesses and ensuring mental health is fully integrated into maternal care, Georgia can take meaningful steps toward reducing maternal mortality statewide.

Bibliography

[1] Alker, Joan. “Georgia’s Women of Reproductive Age Face Many Barriers to Health Care.” Center for Children and Families, March 21, 2025. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2022/08/10/georgias-women-of-reproductive-age-face-many-barriers-to-health-care/.

[2] Children’s National. “An Integrated Approach to Address Perinatal Mental Health Treatment - Children’s National.” Innovation District, January 11, 2022. https://innovationdistrict.childrensnational.org/an-integrated-approach-to-address-perinatal-mental-health-treatment/.

[3] Dossett, Emily C., Alison Stuebe, Twylla Dillion, and Karen M. Tabb. “Perinatal Mental Health: The Need for Broader Understanding and Policies That Meet the Challenges.” Health Affairs 43, no. 4 (April 1, 2024): 462–69. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01455.

[4] Emory University. “Emory Program Supports GA Women With Postpartum Mental Health Issues | Emory University | Atlanta GA,” May 12, 2021. https://news.emory.edu/stories/2021/05/jjm_maternal_health_peace_for_moms/index.html?utm_source=together.emory.edu&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=Advancement%253Aand%253AAlumni%253AEngagement.

[5] Georgia Department of Public Health. “Maternal Mortality,” March 5, 2025. https://dph.georgia.gov/maternal-mortality. “Georgia General Assembly,” April 4, 2025. https://www.legis.ga.gov/legislation/70848.

[6] GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH. (n.d.). MATERNAL MORTALITY REPORT 2019 - 2021.

[7] Hemstad, Mia. “Maternal Mental Health Conditions and Statistics: An Overview — Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance: MMHLA.” Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance: MMHLA, October 29, 2024. https://www.mmhla.org/articles/maternal-mental-health-conditions-and-statistics.

[8] Kaza, Pranitha S. “Unveiling the Challenges and Solutions: A Scoping Review of Maternal Healthcare Access in Rural Georgia.” Cureus, February 18, 2025. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.79238.

[9] Kondracki, Anthony J, Wei Li, Manouchehr Mokhtari, Bhuvaneshwari Muchandi, John A Ashby, and Jennifer L Barkin. “Pregnancy-related Maternal Mortality in the State of Georgia: Timing and Causes of Death.” Women S Health 20 (January 1, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057241267103.

[10] Kousouris, Abby. “Mobile Mental Health Clinic Traveling Across Georgia.” Https://Www.Atlantanewsfirst.Com, July 24, 2024. https://www.atlantanewsfirst.com/2024/07/24/mobile-mental-health-clinic-traveling-across-georgia/.

[11] Schaefer, Ana J., Thomas Mackie, Ekaanth S. Veerakumar, Radley Christopher Sheldrick, Tiffany a. Moore Simas, Jeanette Valentine, Deborah Cowley, Amritha Bhat, Wendy Davis, and Nancy Byatt. “Increasing Access to Perinatal Mental Health Care: The Perinatal Psychiatry Access Program Model.” Health Affairs 43, no. 4 (April 1, 2024): 557–66. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01439.